Chapter 6: The search

The search for a solution, the grace and mercy of God, and the promised servant-king

[ Index | (i) Background: 1 / 2 / 3 | (ii) Problem: 4 / 5 / 6 | (iii) Solution: 7 / 8 / 9 ]

In Chapter 5 we considered something of the nature of the problem of sin as exemplified in Genesis 3. The rest of the Old Testament, from Genesis 4 onwards, might reasonably be titled “In search of a solution” or, more specifically, “In search of the serpent-crusher”. As we shall see in this chapter, the Bible tells the story of people chosen by God to fulfil his purposes. It is a story that both demonstrates the problem of sin and points forward to the solution that God will in due course provide. And it is a story that provides vital context for understanding and recognising that solution when it comes.

6A. The search for a solution

The rise of a great nation

The promise of blessing

After the rebellion of Adam and Eve in Genesis 3, things go from bad to worse: in Genesis 4, Adam and Eve’s first child Cain kills his younger brother Abel. And while “at that time men [do begin] to call on the name of the Lord [i.e. God]” (Genesis 4:26), it is not long before the wickedness of humanity becomes so bad that God resolves to “wipe mankind… from the face of the earth” (Genesis 6:5-7). Only Noah and a few others are spared God’s judgement in the ensuing flood. And while God makes a covenant with Noah (Genesis 9:8ff) promising that there will never again be such a flood, human beings remain in defiance of their creator, as illustrated by the account of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11).

As yet, there is no sign of the promised serpent-crusher, but in Genesis 12:1-7ff there is a very significant development. God calls a man named Abram (later known as Abraham, cf. Genesis 17:1-5), saying “Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you.” Although Abraham and his wife Sarah are very old and have no children, God promises Abraham: “I will make you into a great nation, and I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing… all peoples on earth will be blessed through you.” It is not only that Abraham will be blessed but that all peoples on earth will be blessed through him. God goes on to promise Abraham that his descendants will be given the land of Canaan. This promise is confirmed in God’s covenant with Abraham in Genesis 15, and it is renewed and reiterated throughout the Old Testament. It is not like a modern contract which is typically the product of a lengthy negotiation between two parties. This covenant is determined unilaterally by God.

Around twenty-five years after God’s initial promise, a son, Isaac, is eventually born to Abraham and Sarah. In due course, Isaac’s son Jacob – also known as Israel, cf. Genesis 32:22-28 – has twelve sons, and their descendants become the twelve tribes of the nation of Israel. One of these sons, Joseph, is sold by his brothers as a slave but providentially becomes a leading figure in the Egyptian government. In due course, Joseph’s brothers and their families join him in Egypt.

Freedom from slavery

Over several hundred years the Israelites grow from an extended family of seventy to become “so numerous that the land was filled with them” (Exodus 1:7). The Egyptians, sensing a growing threat (Exodus 1:8ff), oppress the Israelites and force them into slavery.

God has not forgotten his people and his promises though (cf. Exodus 2:24-25, Exodus 3:7-10), and he raises up Moses, an Israelite providentially brought up in the Egyptian royal household. And after more than 400 years in Egypt, just as God had promised Abraham in Genesis 15:13-14, it is Moses, at the age of eighty, who leads the Israelites out of Egypt. This is the “Exodus” – literally “way out” – after which the second book of the Bible is named.

Egypt’s leader Pharaoh repeatedly refuses to let God’s people leave the country. In response, God sends a series of ten plagues, culminating in the plague on the firstborn (Exodus 11:1ff). In contrast, God’s people are spared this judgement and freed from slavery, not because of the good things that they do but because of the blood of a sacrificial lamb “without defect” (Exodus 12:5). This is the first “Passover”, so called because God “passed over” the houses of the Israelites (Exodus 12:27).

Having rescued the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, God provides for them in the desert. Despite their grumbling, he rains down “bread from heaven” (Exodus 16:4) and brings them to Mount Sinai. Here God renews his covenant with his people and gives them his law (Exodus 19:1ff): the Ten Commandments plus additional laws and instructions for how the law is to be applied.

The law is intended to be a source of blessing for God’s people (cf. Deuteronomy 6:1-3, Deuteronomy 28:1ff, Deuteronomy 32:44-47). They have been slaves in Egypt and presumably have no formal legal system of their own. Among other things, the law given through Moses – often called “the Law” – provides a legal framework not least to limit vengeance and to guard against rough justice (cf. e.g. Exodus 21:23-25).

The Israelites are to obey God’s laws as their part of the covenant. God’s people are to “be holy because [God is] holy” (Leviticus 19:2). Some of the laws, such as the food regulations in Leviticus 11:1-47, are specific to Israel’s situation. The New Testament makes it clear that they no longer apply (cf. Mark 7:19, Acts 10:9-11:18). But much of the Old Testament law, and especially the principles behind it, can reasonably be applied generally to God’s people throughout history. It is worth noting that (a) that there are two particularly great commandments that undergird and transcend the whole Old Testament law (including the Ten Commandments); and (b) that these two commandments are reiterated in the New Testament, e.g. in Matthew 22:37-39: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind” (the “first and greatest commandment”, originally from Deuteronomy 6:5); and “Love your neighbour as yourself” (“the second [greatest commandment]”, originally from Leviticus 19:18).

Sacrifices of atonement

Given the nature of the two greatest commandments, and given what we have already noted concerning the Fall, it is unsurprising that God’s people fail to keep their part of the covenant. Indeed even while Moses is still receiving the Ten Commandments, the Israelites make a golden calf to worship (Exodus 32:1-7ff), thus breaking the first two.

Such disobedience evidently comes as no surprise to God, for in his law he makes detailed provision for what is to happen when the people sin (see e.g. Exodus 25:1ff, Leviticus 1:1ff). The Israelites are instructed to build a tabernacle – a large portable tent, three times as long as it is wide. Two-thirds of the tabernacle are separated from the other third, which is not only a perfect square but a perfect cube (1 Kings 6:20). The outer chamber – the larger one – is known as the Holy Place. The inner chamber – the smaller, cube-shaped one – is known as the Most Holy Place or Holy of Holies. This particularly special area is separated from the rest of the tabernacle by a curtain (sometimes called a veil). The tabernacle itself is surrounded by a courtyard in which there is a great altar on which animal sacrifices are burned.

Inside the Most Holy Place is a box known as the ark of the covenant, containing, among other things, a copy of the Ten Commandments. This box is used on the annual Day of Atonement, a particularly notable day of sacrifice described in Leviticus 16. The high priest – the mediator between God and his people – is to take two male goats. The first goat is to be killed for a sin offering, and its blood sprinkled on the ark of the covenant behind the curtain of the Most Holy Place. A life is sacrificed to “make atonement [i.e. amends]” for the sins of the people, “whatever their sins have been” (Leviticus 16:16). As God puts it in Leviticus 17:11, “the life of a creature is in the blood, and I have given it to you to make atonement for yourselves on the altar; it is the blood that makes atonement for one’s life.”

Having sacrificed the first goat, the high priest is “to lay both hands on the head of the [second] goat and confess over it all the wickedness and rebellion of the Israelites – all their sins… [and] send the goat away into the desert…” (Leviticus 16:21). This “scapegoat” is thus a symbol of the sin of God’s people being taken away.

These rituals appear strange, particularly to those of us living in the modern secular world, but the details are very important and we shall return to discuss some of them further in due course. For now we may note that the sacrifices of atonement are an integral part of life for God’s people. They have been rescued for relationship with God, but they are dependent on the system of sacrifices that God provides. The Old Testament animal sacrifices demonstrate the seriousness of sin. The Day of Atonement is a particularly graphic reminder. Deviation from what God had prescribed results in death. Only the high priest can enter the Most Holy Place, and only on one day of the year, and only when blood has been shed. But as we shall see, the Old Testament animal sacrifices cannot take away sins. They are a temporary provision pointing forward to something greater that is yet to come.

A great king

As the Israelites approach the promised land, they continue to grow in number (cf. Numbers 1:1ff). They also continue to rebel, to the extent that God decrees that almost all of the generation who escaped from Egypt will die during a forty year period of wandering in the desert (Numbers 14:21-35). It is under the leadership of Joshua rather than Moses that the next generation eventually enters and conquers the promised land of Canaan (Joshua 1:1ff) as God had promised Abraham. At this stage we see something resembling God’s people living in God’s place under God’s rule. This does not last long though, and the serpent-crusher is still nowhere to be seen.

After Joshua dies, the next generation of Israelites turn to other gods and there is a general decline (Judges 2:10-19). God raises up a series of “judges” (leaders) to save Israel, but after the death of each judge God’s people again fall into sin. This cycle runs through the book of Judges, which ends with something of a state of anarchy where “everyone [does] as he [sees] fit” (Judges 21:25, cf. Judges 17:6).

With the promised serpent-crusher still nowhere to be seen, God raises up Samuel as the judge of Israel, and the people return to serving God (1 Samuel 7:2ff). Samuel’s sons do not walk in their father’s ways though (1 Samuel 8:1ff), and the elders of Israel ask Samuel for a king such as all the other nations have. In essence, this is a rejection of God as their rightful king, something that God had warned his people about when he gave his law to Moses (Deuteronomy 17:14ff). But after reiterating his warning of the consequences, God grants his people their request.

After a faltering start under Saul, God chooses David, a mere shepherd boy, born in Bethlehem as the youngest of eight brothers, to be the next king of Israel (1 Samuel 16:1ff). In due course the covenant is renewed (2 Samuel 7:8-17), and King David unites the twelve tribes, establishes a capital city, secures Israel’s borders and sets up an organised administration.

David is a great king, “a man after [God’s] own heart” (Acts 13:22, cf 1 Samuel 16:7) who “[reigns] over all Israel, doing what [is] just and right for all his people” (2 Samuel 8:15). Again we see something resembling God’s people living in God’s place under God’s rule. But David is not without his weaknesses, a theme to which we shall return, and he is evidently not the promised serpent-crusher.

Division, decline and exile

In due course David is succeeded by his son Solomon (1 Kings 1:28ff). In some respects this marks the high point of the Old Testament. God’s people are “asnumerous as the sand on the seashore” – just as God had promised Abraham (e.g. Genesis 22:17, cf. Genesis 15:4-5) – and “they [are] happy” (1 Kings 4:20). God’s people have a permanent place to live, and Solomon builds a magnificent temple in Jerusalem (1 Kings 6:1ff) as a more permanent home for the Most Holy Place.He is blessed by God and is “greater in riches and wisdom than all the other kings of the earth” (1 Kings 10:23-24, cf. 1 Kings 4:29-34).

But Solomon also has weaknesses. In particular, he acquires for himself great material wealth and takes many wives, something which God has expressly forbidden (Deuteronomy 17:16-17). Moreover, many of these wives are from other nations, despite God having told the Israelites, “You must not intermarry with [these nations], because they will surely turn your hearts after their gods” (1 Kings 11:1-6ff). This marks the beginning of a terminal decline for the nation of Israel. After Solomon’s son Rehoboam becomes king there is a rebellion and the kingdom of Israel becomes divided into two parts: the ten northern tribes, somewhat confusingly still called “Israel”, with Samaria as its capital; and the two southern tribes, known as “Judah” (the name of one of the two tribes), with Jerusalem as its capital.

There follows a steady decline in the fortunes of both Israel and Judah, despite the ministry of the prophets who bring from God warnings of judgement and messages of hope. Many of the kings of both Israel and Judah fail to follow in God’s ways, beginning with the idolatry of Jeroboam (1 Kings 12:25-33) and Rehoboam (1 Kings 14:21-24). Although there are some relatively “good” kings, e.g. Hezekiah, God’s people end up being exiled as a result of God’s judgement on their disobedience (cf. Deuteronomy 28:15ff).

Around 722 BC the people of the northern kingdom of Israel are exiled to Assyria, the superpower of the time, and Israel ceases to be an independent state (2 Kings 17:1ff). Around 597 and 586 BC the people of Judah are exiled to Babylon, the next superpower. Jerusalem is captured and plundered, and many of its buildings destroyed, including the temple (2 Kings 25:1ff, cf. Jeremiah 39:1ff, Lamentations 1:1ff). In a telling echo of Genesis 3:23-24, we are told that “it was because of the Lord’s anger that all this happened to Jerusalem and Judah, and [that] in the end he thrust them from his presence” (Jeremiah 52:3).

While Cyrus of Persia later allows the exiles to return after the fall of the Babylonian empire, those who do return (“the remnant”) struggle to reconstruct the state of Judah. Jerusalem is eventually rebuilt and the temple reconstructed (Ezra 1:1ff, Nehemiah 1:1ff), but the Old Testament ends with Judah as a shadow of what the original kingdom of Israel had been under David and Solomon (cf. Haggai 2:3). God’s people are relatively few in number and beset by difficulties, not least in the shape of their own half-heartedness and sin. The problem remains, and the serpent-crusher is still nowhere in sight.

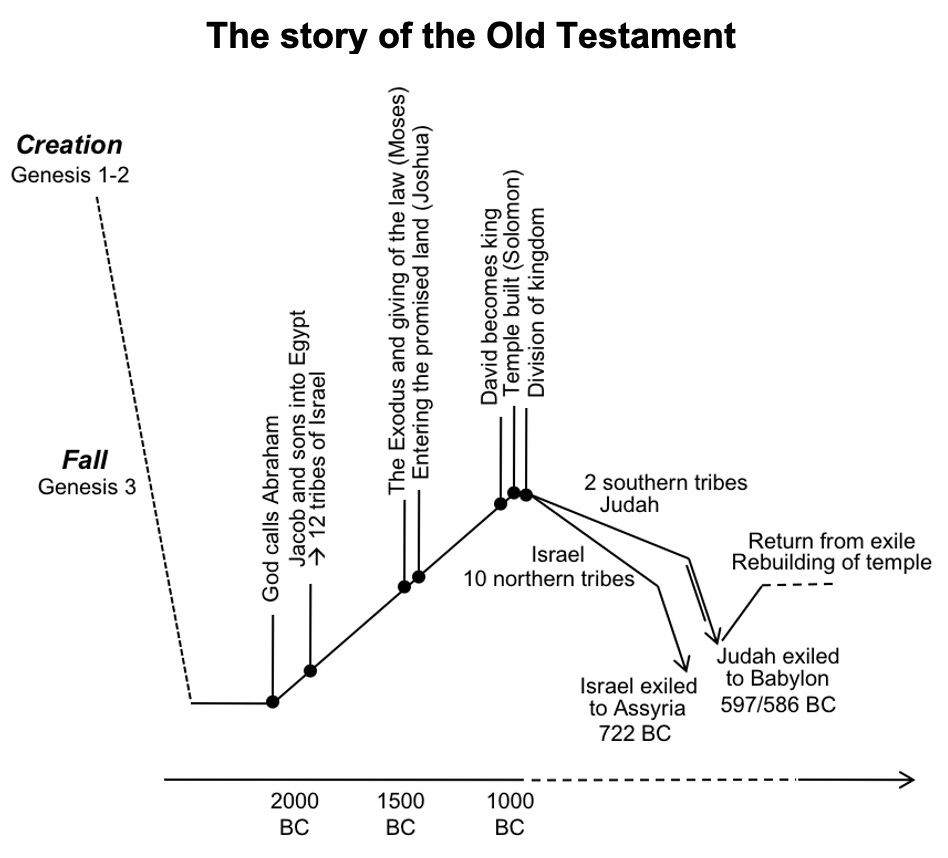

The story of the Old Testament can be summarised on a schematic diagram such as that below.

The problem remains…

The problem emphasised

The events of the Old Testament, played out over more than 1500 years, do not solve the problem of sin. Instead they serve to demonstrate and to emphasise its seriousness and its universal nature. Then as now, the problem of sin transcends times and cultures.

Even the greatest characters of the Old Testament follow the pattern of Genesis 3. Abraham, encouraged by his wife Sarah, appears to doubt what God has said, and seeks to fulfil God’s promise of descendants by sleeping with Hagar, Sarah’s maidservant (Genesis 16:1ff). Two generations later, Jacob uses deception to obtain his brother Esau’s birthright (Genesis 25:19ff). Of Jacob’s twelve sons, born to four different women, one sleeps with his father’s concubine (Genesis 35:22) and another sleeps with his own daughter-in-law (Genesis 38:1ff). And as a group, the older brothers (probably ten of the twelve) toy with the idea of murdering the eleventh before deciding to sell him into slavery instead (Genesis 37:12ff). It is remarkable that these twelve men are the founders of the nation of Israel.

This theme continues throughout the Old Testament. Moses, for example, is a great leader and prophet, but he is also a murderer (Exodus 2:11-12) who is sometimes openly reluctant to obey God (Exodus 4:13). His older brother Aaron, chosen to speak for God and to be the first high priest, is instrumental in fashioning the golden calf (Exodus 32:1-7 again). David is a great king and prophet, but, after seeing the beautiful Bathsheba bathing, he commits adultery with her. He then arranges for her husband Uriah to be killed (2 Samuel 11:1ff). Solomon is an extraordinarily wise king, but his idolatry leads to the break-up of the nation of Israel (1 Kings 11:29-33). Etc. The leaders of God’s people – prophets, priests and kings – serve only to emphasise the seriousness and the universal nature of the problem of sin.

Similar comments may be made of the people of Israel as a whole. Among many other things, the Israelites are quick to grumble and to turn to other gods (cf. e.g. Exodus 16:2, 1 Samuel 8:4-8). Throughout the Old Testament, the problem of sin is evident both in the lives of individuals and in the corporate life of the nation of Israel. And just as in Genesis 3, sin has consequences: the judgement of God.

As we noted in the previous chapter, the link between sin and judgement is not necessarily straightforward. God’s judgement is sometimes immediately evident, but more often it is delayed (see e.g. Deuteronomy 28:15ff and 2 Kings 25:1-21), sometimes until the promised final judgement (see e.g. Isaiah 66:1-24, Joel 3:1-16, Malachi 4:1-3). But in any case, the message of the Old Testament is that the question of how we can escape God’s judgement remains unanswered. The terrible prospect of the “day of the Lord” described so vividly by the prophets of the Old Testament (e.g. Joel 1:15ff, Amos 5:18ff, Malachi 4:1ff) serves only to emphasise the problem.

The problem unsolved

As the Old Testament ends, the problem of sin remains unsolved, and a solution appears to be as far away as ever.

While Abraham has become the father of a great nation with many descendants, and while the Israelites have inherited the land of Canaan, the remnant of Judah is but a shadow of the former kingdom. And while some non-Jews have been blessed through the nation of Israel – examples include Rahab (Joshua 2:1ff), Ruth (Ruth 1:16, Ruth 4:13-22) and Naaman (2 Kings 5:15) – it can hardly be said of the Old Testament nation of Israel that “all peoples on earth [have been] blessed through them” (Genesis 12:3).

While God has delivered his people from slavery in Egypt, they remain slaves to sin. The law serves to illustrate the extent of the problem rather than to provide a solution. In the words of Deuteronomy 27:26, “Cursed is anyone who does not uphold the words of this law by carrying them out.”

While God has generously provided a system of sacrifices to be enacted when his people sin, these rituals do not actually solve the problem. While the Old Testament sacrifices provided a graphic illustration of the link between sin and death, they were merely a “...reminder of sins, because it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins” (Hebrews 10:3-4, cf. Romans 3:25-26). It is only human blood, i.e. human death, that can atone for human sin (cf. Leviticus 17:11 again). “Without the shedding of [human] blood there is no forgiveness” (Hebrews 9:22). The purpose of animal sacrifices was never to solve the problem of sin but to remind people of its seriousness.

And while David was a great king, chosen by God to rule over his people, he was also a fallible human being, as we have seen. Like Saul before him, like the kings who came after him, and like the subjects of his kingdom, David could not offer a solution to the problem of sin.

…but the search is not over

We have seen that the Old Testament serves to emphasise rather than to solve the problem of sin. But while the promised serpent-crusher has not yet arrived, it is a mistake to think that God will not now deliver on his promises. God sees human history from a perspective that is very different from our own. He does not just take the long view; he has an eternal view that transcends time. He knows the past, he knows the present, and he knows the future. We noted earlier that God promised Abraham that the Israelites would be in slavery in Egypt for more than 400 years. Moses, who knew better than most the resultant frustration of the Israelites, was thus well-placed to write that “a thousand years in [God’s] sight are like a day that has just gone by” (Psalm 90:4). God always keeps his promises, but he does so on his timescale.

When the Old Testament is carefully considered, it is evident that God is in control of events. A particularly striking example of this can be seen in the life of Joseph. Although Joseph’s brothers sell him into slavery so as to be rid of him (Genesis 37:12ff), God is working through events to take his people where he wants them to go. At the end of Genesis, after Joseph’s family have joined him in Egypt, he says to his brothers, “You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good to accomplish what is now being done, the saving of many lives” (Genesis 50:20, cf. Genesis 45:4-8). Surprising though it may be, it is the recurrent testimony of Scripture that God works out his purposes in the lives of individuals, and that he sometimes does so in the face of terrible suffering, a theme to which we shall return.

6B. The grace and mercy of God

We noted earlier the many failings of God’s chosen people. Again and again they did things that deserved God’s judgement. And God’s judgement was often what they got. But we also see again and again God’s grace and mercy – his grace in giving his people what they do not deserve, and his mercy in not giving his people what they do deserve. God loves his people and, remarkably, he works through human sin and rebellion to bring about his purposes.

The grace and mercy of God are evident throughout the Old Testament. In the previous chapter we noted hints of God’s grace and mercy even in the context of the judgement of Genesis 3. In Genesis 4 we see more of God’s grace and mercy in the birth of further children to Adam and Eve. And while God rightly punishes Cain for the murder of his brother Abel, we see that Cain is protected by God “so that no one who found him would kill him” (Genesis 4:15). Several chapters later, it is because of God’s grace and mercy that he spares Noah and his family from the great flood, and promises that there will “never again be [such] a flood” (Genesis 9:11).

It is because of God’s grace and mercy that he calls Abraham and gives him an unconditional promise of blessing. Abraham is not chosen because he is notably worthy. Indeed we learn later that he was a member of a family that “worshipped other gods” (Joshua 24:2).

It is because of God’s grace and mercy that God brings Jacob’s family to Egypt so that they do not starve. It is because of God’s grace and mercy that the people of Israel are set free from slavery in Egypt. They are spared judgement not because they have behaved particularly well but because of God’s provision of the blood of an unblemished sacrificial lamb. And when God renews his covenant at Mount Sinai, it is because of his grace and mercy that he gives his people the law that is intended to be for them a source of great blessing.

It is because of God’s grace and mercy that he makes provision in his law for dealing with his people’s sin, at least up to a point. The Old Testament sacrifices are an ongoing reminder of God’s grace and mercy to his people.

It is because of God’s grace and mercy that he brings his people into the promised land of Canaan despite their rebellion. It is because of God’s grace and mercy that he repeatedly raises up judges for his people when they turn to serve other gods. And it is because of God’s grace and mercy that when the people of Israel reject him as king, he gives them Saul – who is not altogether a bad king – and then the great king David.

Even in the context of the exile of God’s people we can see his grace and mercy. He sends his prophets with messages not just of judgement but of hope. In his grace and mercy, God permits a return from exile for the people of Judah. As the Old Testament ends, all is not lost. Indeed the stage is set for God’s ultimate expression of grace and mercy. From the remnant who returned from exile, the serpent-crusher is yet to come.

6C. The promised servant-king

God’s promised servant

The Old Testament provides various pointers to the identity of the serpent-crusher. Consider for example the “servant songs” of the prophet Isaiah.

In the first servant song, in Isaiah 42, God says, “Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen one in whom I delight; I will put my Spirit on him, and he will bring justice to the nations. He will not shout or cry out, or raise his voice in the street… In his teaching the islands will put their hope.” He speaks of making this servant “a light for the Gentiles, to open eyes that are blind, to free captives from prison, and to release from the dungeon those who sit in darkness” (Isaiah 42:1-7). And while these verses were written originally to Israel, and to some degree apply to the Israelite nation as the servant, it becomes evident from the New Testament that these verses also refer to another servant of God.

In the second servant song, in Isaiah 49, God speaks similarly of making his servant “a light for the Gentiles, that [his] salvation would reach the ends of the earth” (Isaiah 49:6). And he goes on to describe a “day of salvation” (Isaiah 49:8).

In the third servant song, in Isaiah 50, God speaks of one who has “not been rebellious”, who “[offers] his back to those who beat him”, and who “[does] not hide [his] face from mocking and spitting” (Isaiah 50:5-6). And God promises that this same person will be vindicated as someone whom no one can condemn (cf. Isaiah 50:8-9).

But it is in the fourth servant song, beginning at Isaiah 52:13, that we find perhaps the most remarkable words concerning the servant of God. This passage is worth quoting at length for reasons that will become clear later: “He was despised and rejected by men, a man of sorrows, and familiar with suffering. Like one from whom men hide their faces he was despised, and we esteemed him not. Surely he took up our infirmities and carried our sorrows, yet we considered him stricken by God, smitten by him, and afflicted. But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was upon him, and by his wounds we are healed. We all, like sheep, have gone astray, each of us has turned to his own way; and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all. He was oppressed and afflicted, yet he did not open his mouth; he was led like a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is silent, so he did not open his mouth... he was cut off from the land of the living; for the transgression of my people he was stricken… though he had done no violence, nor was any deceit in his mouth. Yet it was the Lord’s will to crush him and cause him to suffer, and though the Lord makes his life a guilt offering, he will see his offspring and prolong his days… After the suffering of his soul, he will see the light of life and be satisfied… my righteous servant will justify many, and he will bear their iniquities. Therefore I will give him a portion among the great… because he poured out his life unto death, and was numbered with the transgressors. For he bore the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors” (Isaiah 53:3-12).

We shall see in due course that the servant songs of Isaiah, written around 700 BC, provide an extraordinary foreshadowing of God’s solution to the problem of sin.

God’s promised king

We get some more pointers as to the identity of the serpent-crusher from God’s promises concerning a particularly special king.

Consider for example a promise that God makes to David in the context of David’s desire to build a temple for God. Through the prophet Nathan, God says to David, “When your days are over and you go to be with your ancestors, I will raise up your offspring to succeed you, one of your own sons, and I will establish his kingdom. He is the one who will build a house for me, and I will establish his throne for ever. I will be his father, and he will be my son...” (2 Chronicles 17:11-13). In contrast to the kings of the Old Testament who were imperfect and mortal, God is promising a king who will rule perfectly over God’s people and who will live forever.

Along with God’s promise to Abraham, this is one of the most significant promises of the Old Testament. It is repeatedly echoed through the prophets. Through Jeremiah, God declares: “The days are coming… when I will raise up to David a righteous Branch, a King who will reign wisely and do what is right and just in the land… [who] will be called: The Lord Our Righteous Saviour” (Jeremiah 23:5-6). In the book of Isaiah we find these words, often read at Christmas: “For to us a child is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders. And he will be called Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his government and peace there will be no end. He will reign on David’s throne and over his kingdom, establishing and upholding it with justice and righteousness” (Isaiah 9:6-7). And Daniel speaks similarly of God establishing “a kingdom that will never be destroyed… it will… endure forever” (Daniel 2:44).

This promised eternal kingdom will be unlike any other – and so will its king. Zechariah speaks of the king of God’s people coming to them “righteous and victorious [but] lowly and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey” (Zechariah 9:9). And Micah speaks of the coming of another shepherd-king from Bethlehem who will be “ruler over [God’s people]” and “whose origins are from old, from ancient times” (Micah 5:2-4).

Through this king, all peoples on earth will be blessed, just as God had promised Abraham. This king will rescue people not just from slavery to their oppressors but from slavery to sin. This king will provide a permanent and effective remedy for sin. This king will be a perfect king, the King of kings, who will live forever.

We shall see in due course that the Old Testament prophecies concerning this particularly special king, written hundreds of years before Jesus was born, provide an extraordinary foreshadowing of God’s solution to the problem of sin.

God’s promised servant-king

God’s people could thus live in the hope and expectation of the arrival of the serpent-crusher. This person will be a sinless servant who will die in his mission and yet live again. This person will be the King of kings. And through this promised servant-king, God will bring salvation to his people.

Next chapter (Chapter 7)

Outline of whole book for reference

Part (i): Background

Part (ii): Problem

Part (iii): Solution

Main index with additional outline structure

The Big Reveal homepage (or search Substack for “The Big Reveal”)

Text © The Big Reveal 2024