Chapter 5: The problem

The pattern of rebellion, the necessity of justice, and the inevitable consequences

[ Index | (i) Background: 1 / 2 / 3 | (ii) Problem: 4 / 5 / 6 | (iii) Solution: 7 / 8 / 9 ]

In Chapter 4 we discussed the context for the problem that God has revealed. In this chapter we shall consider the problem itself.

5A. The pattern of rebellion

Genesis 3

Context

We have seen how the first two chapters of Genesis present a picture of paradise: an ordered and purposeful world created by a good God in which his people live in his beautiful and bountiful place under his perfect rule. But in the third chapter of Genesis, in the account of what is often called “the Fall”, we find things going badly wrong. Before we consider what this passage says, it is worth emphasising again the importance of a careful consideration of both context and genre.

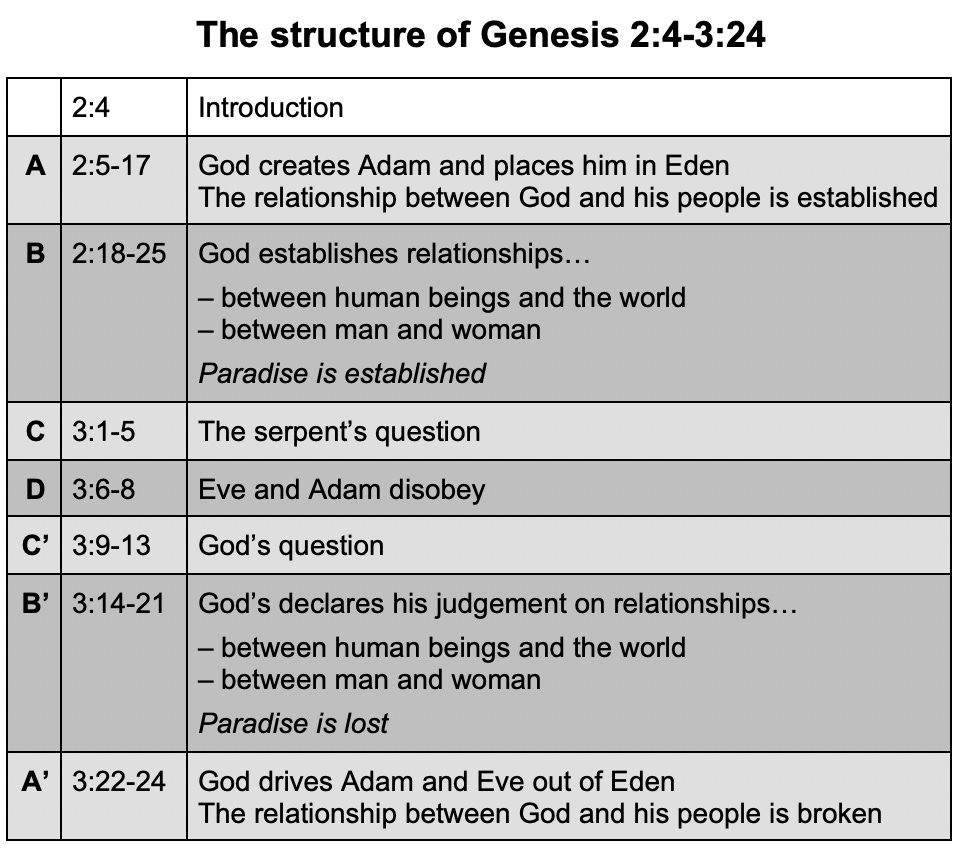

In terms of context, Genesis 3 forms part of “the account of the heavens and the earth when they were created” (Genesis 2:4ff). Within this account, the first of Genesis’ main sections, there are three distinct narratives: the Garden of Eden (Genesis 2:5-3:24), the murder of Abel (Genesis 4:1-16) and Cain’s family (Genesis 4:17-26). For the purposes of this discussion we shall focus on the first of these, an outline of which is set out in the table below. Like the Genesis prologue, the text of Genesis 2:4-3:24 as a whole can be considered as having a well-defined structure – in this case the symmetrical ABCDC’B’A’ form as shown in the left-hand column.

Genre

In terms of genre, we have already noted that Genesis 2:4-25 is written in a vivid and memorable way, borrowing imagery from other writings of the time. Much the same can be said of Genesis 3, and the talking serpent should be viewed with this in mind.

If we accept that with God “all things are possible” (Matthew 19:26), we should exercise caution in saying that the serpent is definitely figurative. Yet at the same time we may note that the book of Revelation – a part of the Bible full of graphic imagery and symbolism (cf. e.g. Revelation 4:1-8) – speaks of “that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the world astray” (Revelation 12:9). But in any case it matters less whether the serpent is real, and rather more what the serpent is described as saying.

Similar comments can be applied to the “tree of life” and, by implication, to the “tree of the knowledge of good and evil” (Genesis 2:9ff; Revelation 2:7, Revelation 22:2ff). We may note too that the phrase “tree of life” is used several times in the book of Proverbs (Proverbs 3:18, Proverbs 11:30, Proverbs 13:12, Proverbs 15:4), and that in each case a non-literal meaning is intended.

That said, it is important to observe that a figurative literary device can be a legitimate and effective way to convey actual truth. In the Old Testament this is evident e.g. from the prophet Nathan’s rebuke to David (2 Samuel 12:1ff). In the New Testament it is particularly apparent in the parables told by Jesus. We may note too that a figurative reading of Genesis 3 does not necessarily preclude Adam and Eve from being historical figures. Nor does it render Satan – or God – any less real. With these observations in mind, we turn now to the text.

The Garden of Eden (part 1)

Genesis 2:5-25 sets the scene for Genesis 3. Of particular importance is Genesis 2:16-17 where God says to Adam, “You are free to eat from any tree in the garden; but you must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat of it you will surely die.” At the end of Genesis 2, God’s people are free to eat from almost every tree in the garden. There is only one tree from which they cannot eat.

Genesis 3 begins with a description of the serpent as “more crafty than any of the wild animals the Lord God had made” (Genesis 3:1). The writer is implicitly inviting the reader to examine carefully what the serpent is saying and doing in the exchange that follows.

There follows a dialogue between the serpent and the woman who is later named as Eve (Genesis 3:20). The serpent asks, “Did God really say, ‘You must not eat from any tree in the garden’?” (Genesis 3:1 again). Already we can see the serpent’s craftiness. He begins not by saying that God is wrong or that he should not be obeyed, but by questioning what he says. And by the phrasing he uses, the serpent plants the suggestion that God has been more restrictive than he actually has.

While Eve replies (correctly) that she and Adam “may eat fruit from the trees in the garden,” she then goes on to say that God said “You must not eat fruit from the tree that is in the middle of the garden, and you must not touch it, or you will die’” (Genesis 3:2-3, emphasis added). Whereas God forbade only eating the fruit, Eve has added to his command by saying that touching it is also forbidden. Perhaps subconsciously influenced by the serpent, Eve makes out that God has been more restrictive than he actually has.

The serpent then switches strategy and says to Eve, somewhat ambiguously, “You will not surely die,” before adding, “your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:4-5). The combination of the serpent’s guile with the visual appeal and desirability of the fruit is sufficient to persuade Eve to “[take] some and [eat] it. She also gave some to her husband [Adam], who was with her, and he ate it” (Genesis 3:6). In Genesis 2, there was only one thing that God had commanded Adam not to do. Six verses into Genesis 3, both he and his wife had done it. We shall return to the subsequent verses in due course.

A universal human trait

We noted earlier that human beings have a sense of right and wrong. We find something inside us somehow telling us that we ought to adhere to certain standards of behaviour. Consciously or otherwise, human beings everywhere appeal to a law of right and wrong, or what some people call the moral law. We have a sense of how we ought to behave, and we expect other people to recognise and respect it. These observations are consistent with human beings being made in the image of a holy God.

Closely related to our sense of right and wrong is another universal human experience: other people do not live up to the standards that we expect of them. We are very quick to recognise this of course, but, for reasons that we shall come to, we are rather slower to recognise that we do not live up to the standards that others expect of us. (If you have any doubt about this, ask anyone who knows you well – if you dare!) But the bottom line is that when it comes to observing the law of right and wrong, we all fall short, at least to some degree.

In the discussion that follows we shall see that these observations are consistent with God’s revelation in the Bible. In the previous chapter, we noted that God created people with the capacity to relate to him, and that he has given all of us – individually and collectively – responsibility for the world that he has made. As such, and whether we recognise it or not, we are accountable to him for our actions. God does not compel us to act as he has commanded though. He permits us to rebel against him, to do as we please, and to disobey his commands. And one way or another, that is what happens, at least to some degree.

Among other things, Genesis 3 illustrates this universal human trait. As we shall see, the human rebellion against God that is exemplified by Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden is a recurring theme throughout the Bible and indeed all human history. As we have already noted, the Hebrew word for man is also the name Adam (cf. e.g. Genesis 2:7,20). It is thus implicit from the Genesis account that Adam is a representative of the human race, a theme that is picked up in the New Testament (see e.g. Romans 5:12ff, 1 Corinthians 15:22). All of us are identified with Adam both in our humanity and in our rebellion against God. And it is this rebellion, putting ourselves first rather than God first, and living our own way rather than God’s way, that is at the root of what is described in the Bible as sin.

The nature of sin

The breakdown of relationship

The way in which the word “sin” is used varies widely. At one end of the spectrum, “sin” is now often used to convey an enjoyable but essentially harmless indulgence of which only a puritanical killjoy could disapprove. For example, we speak of taxes on items such as beer and wine as “sin taxes”. In contrast, and at the other end of the spectrum, the word “sinful” is often reserved for the most serious crimes.

On this basis, we can understand why relatively few people today would consider themselves sinful. At one end of the scale, eating a “naughty-but-nice” cream cake is plainly not intrinsically sinful, even if it is washed down with a glass of wine. And at the other end of the scale, most of us will never commit those crimes for which the word “sinful” is often reserved. But as we shall see, the ways in which the words “sin” and “sinful” are used in the Bible are rather different.

At the outset, it is important to dispel the notion that the biblical meaning of sin is intrinsically concerned with sex. Such a link is not found in the Bible. As we have seen, the sin of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden was that they disobeyed God. They ate fruit – the Bible does not say it was an apple – “from the tree that [God] commanded [them] not to eat from” (Genesis 3:11). The increasingly dated phrase “living in sin” that was once commonly used to describe couples living together before marriage is thus misleading at best.

More broadly, it is important to appreciate that sin involves not so much the breaking of rules as the breaking of our relationship with God. It is perhaps a useful coincidence that the word sin has “I” at its centre. For, according to the Bible, one of sin’s primary characteristics is a desire for autonomy – a yearning to decide for ourselves what is right and wrong, and to live our lives without reference to the God who made us. Sin is not necessarily spectacular. The rebellion that it entails may be far from obvious. It may appear as little more than acting as if God were not there. Such a breakdown of relationship is exemplified in the New Testament story of the lost son – or “prodigal son” – who wants the good things that his father can give him, but who walks away from their relationship (Luke 15:11ff).

In general terms, the seriousness of the breakdown of a relationship depends on the nature of that relationship. If I fall out with someone I have just met on holiday, there is relatively little to lose. If I fall out with the person who lives next door, or an old friend, or someone I work with, I have rather more to lose. And if the relationship in jeopardy is that with my wife or my child or my mother or father, there is a great deal at stake. But the seriousness of a breakdown of even the most important of our relationships with other people is dwarfed by the gravity of a breakdown of the relationship with the God who made us and to whom we are ultimately accountable.

The heart of the problem

The breakdown of our relationship with God is intrinsically linked with the state of our hearts. We are made to relate to the God who made us, but our hearts are inclined to embrace things other than our Creator.

Something that displaces God as the object of the affections of our heart is an idol – a counterfeit god. And God cares deeply about the affections of the hearts of his creatures. It is no coincidence that the first two of the Ten Commandments concern idolatry: “[1] You shall have no other gods before me. [2] You shall not make for yourself an image [or idol] in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below” (Exodus 20:3-4, cf. Deuteronomy 4:15-19).

Of course an idol in the modern world is not necessarily so crude as a carved bird or animal. These days our physical idols are more likely to have doors and windows. This is not to say that material wealth is an inherently bad thing. Indeed “nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving” (1 Timothy 4:4). The problem comes when God is displaced in the affections of our hearts. As the New Testament has it, “You cannot serve both God and Money” (Matthew 6:24; NB the word translated Money here – sometimes rendered “Mammon” – conveys riches and greed rather than merely an amount of currency).

A good indication of the nature of our counterfeit gods is what we think about when we have nothing else to think about. Such idolatry may relate to money and material possessions. But more broadly, counterfeit gods come in many forms: achievement, be it in education, in the workplace, on the sports field, or on the stage; relationships, whether with friends, a boyfriend or girlfriend, a husband or wife, or children and grandchildren; leisure, perhaps through holidays, or television and film, or health and fitness, or any of various hobbies. And many more. Again, this is not to say that any of these things are inherently bad. The problem comes when God is displaced in the affections of our hearts.

It is important to recognise that those who are inclined to shun much of the above are not immune from idolatry. It is quite possible and indeed quite common to reject much of what the world offers and yet to fail to seek God. This applies not just to “non-religious” people but to those who would count themselves religious – including Jews and Christians. In the Bible God speaks repeatedly against religious hypocrisy, lamenting “those who come near to me with their mouth and honour me with their lips, but [whose] hearts are far from me… [and whose] worship… is based on merely human rules they have been taught” (Isaiah 29:13, cf. e.g. Jeremiah 12:2, Mark 7:6-7, Luke 11:37-54).

The state of the human heart in rebellion against God is universal. In this fallen world, sinfulness is an intrinsic part of being human (cf. e.g. Psalm 51:5, Romans 5:12ff). We sin because we are inherently sinful. This may jar with the popular notion that people are intrinsically morally good, but it is consistent with what we observe. We do not have to teach our children how to be selfish or disobedient. Irrespective of whether or not we speak of “original sin” – a phrase that is not actually found in the Bible – sinfulness is evident in everybody, everywhere, from a fairly early age. While very young children “do not yet know good from bad” (Deuteronomy 1:39), it is only a matter of time before their sinful nature becomes apparent.

The fact that sinfulness is an intrinsic part of being human does not mean that the effects of sin show up in exactly the same way in everybody’s lives though. Nor does it mean that anyone is as sinful as they could possibly be. But it does mean that every aspect of what we do, say and think is affected by our sinful nature. In the New Testament we read that “it is from within, out of a person’s heart, that evil thoughts come – sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, greed, malice, deceit, lewdness, envy, slander, arrogance and folly. All these evils come from inside and defile a person” (Mark 7:21-23). The “heart” here represents much more than the physical organ. It is the centre of a person’s whole being. And it is from the sinful human heart that bad behaviour originates. Contrary to what some would have us believe, it is the problem – not the solution – that lies within us. At the heart of the problem is the problem of the heart.

Beyond human behaviour

So far, we have considered sin in terms of human behaviour. But while there are many passages in the Bible that speak of sin in this way, there are others where sin is portrayed as something rather less tangible. This is evident from as early as Genesis 4:7 – the first time that the word “sin” occurs in the Bible – where God warns Cain that “sin is crouching at your door; it desires to have you, but you must master it.”

In the New Testament, Paul writes similarly that “sin… produced in me every kind of covetous desire… sin… deceived me… and put me to death” (Romans 7:8,11, cf. Genesis 3:13, Galatians 5:17, Hebrews 3:13). He goes on to use the phrase “sin living in me” repeatedly (Romans 7:17-20). And while there is more to the identity of “me” in these verses than meets the eye – see e.g. John Stott, The Message of Romans, p205ff – it is plain that there is also more to sin than mere human behaviour.

In the Bible, sin is described not only in terms of human activity – or lack of it – but as something that enslaves us, and from which we need to be set free. According to the New Testament, “everyone who sins is a slave to sin” (John 8:34), and “the whole world is a prisoner to sin” (Galatians 3:22, cf. Proverbs 29:6).

5B. The necessity of justice

In the context of the above discussion it should come as no surprise to read that“all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23, cf. e.g. 1 Kings 8:46, Ecclesiastes 7:20, 1 John 1:8). It is a measure of our sinful nature that not only do we often ignore God’s standards and seek to establish our own, but that we do not even consistently live up to the standards that we set for ourselves. Unless our own standards are unusually low, we stand self-condemned quite apart from God’s verdict.

In contrast, God is holy and perfectly good. None of us comes anywhere near to meeting his standards. In the words of Isaiah, “all our righteous acts [tainted as they are by our sinful nature] are like filthy rags” when compared to the holiness of God (Isaiah 64:6). God’s holiness and our sinfulness are difficult for us to grasp. Almost invariably, we are more sinful than we are inclined to think, and God is more holy than we can imagine. And the God who is the very essence of goodness, truth and love cannot tolerate sin, with its evil, lies and hatred. In the poetic words of the Old Testament prophet Habakkuk, God’s “eyes are too pure to look on evil; [he] cannot tolerate wrong” (Habakkuk 1:13, cf. Psalm 5:4). As we noted earlier, God is a God of justice. He “will not acquit the guilty” (Exodus 23:7, cf. Proverbs 17:15, Isaiah 5:22-23). In God’s world, justice must be done.

On one level, this does not sound too serious. As we noted earlier, we typically long for justice, especially when we are the victims of injustice. When I hear of a crime such as murder, for example, I find myself thinking that those responsible ought to be brought to account. Moreover, I am angry, and I consider myself right to be angry.

In the context of injustice, and particularly a crime such as murder, it should not surprise us that God can get angry too. While he may be “slow to anger” (Exodus 34:6 again, cf. e.g. Psalm 103:8, Joel 2:13), this is not to say that he does not get angry (cf. e.g. Numbers 32:13, Isaiah 5:25, Mark 3:5). But there is an important distinction to be made between righteous anger and (for example) the sort of anger I display when I lose my temper for no good reason. And even if I am right to be angry, my conduct is not always righteous and my motives are not always pure (cf. e.g. Ephesians 4:26). In contrast, God’s anger is always righteous, and it is quite consistent with him being the essence of goodness, truth and love.

As a person made in God’s image, I can understand God’s anger, at least up to a point. I would not want him to overlook a crime such as murder, and to let such an act go unpunished. And in some respects, I am, like many people, inclined to feel that I am on high moral ground in desiring justice in such a case. I have never murdered anyone, and it is unlikely, statistically at least, that I ever will.

But God’s view of the situation is rather different. He is concerned not only with what we do but with what is on our hearts. And according to the New Testament, it is not only that “anyone who murders will be subject to [God’s] judgement… [but] anyone who is angry with his brother” (Matthew 5:21-22, cf. 1 John 3:15). Murder, terrible as it is, is only one of the many results of sin. Anger, i.e. anger of the wrong sort, is another. And as I have already acknowledged, on that count I stand guilty as charged.

This brings us back to the uncomfortable but vitally important fact that we are all guilty of sin. And herein lies the conundrum. I may want justice done, but I am in fact part of the problem not part of the solution. As a sinful human being I tend to think of people being on a sliding scale from very good through to very bad. I am inclined to draw some sort of vague distinction between “good” and “bad” people, and then to put myself into the “good” category. But in reality, and in God’s view, there is no such distinction. “There is no one righteous, not even one” (Romans 3:10, cf. e.g. Psalm 14:3, Proverbs 20:9).

While the symptoms of sin vary, the root cause of sin does not. And in terms of goodness and badness, my sinful anger puts me in the same category as a murderer. My behaviour reflects of the state of my sinful heart, which in turn reflects the breakdown in my relationship with God.

Our desire for justice is a good thing, and it is consistent with our being made in the image of a God of justice. But by God’s standards of justice, all of us are in the dock and all of us are guilty. Whether we like it or not, and whether we believe it or not, we all face God’s judgement.

5C. The inevitable consequences

Paradise lost

The Garden of Eden (part 2)

Back in Genesis 3, the immediate effect of Adam and Eve’s disobedience was that their “eyes… were opened, and they realised they were naked; so they sewed fig leaves together and made coverings for themselves” (Genesis 3:7). This is in stark contrast to Genesis 2:25 where “the man and his wife were both naked, and they felt no shame.”

It soon becomes clear that Adam and Eve’s relationship with God has changed drastically as a result of their sin. According to Genesis 3:8-10, they hid from God, and Adam was afraid. The relationship between Adam and Eve has also been affected. When God asked Adam if he had “eaten from the tree that [he] commanded [him] not to eat from,” he could do no better than pass the buck to Eve, who in turn blamed the serpent for deceiving her (Genesis 3:11-13). Even before God gives his verdict it is clear that things are no longer as they were.

As the rest of Genesis 3 unfolds, the consequences become clearer, as God pronounces judgement, firstly on the serpent, then on Eve, and finally on Adam (Genesis 3:14-19):

God said to the serpent, “Because you have done this, cursed are you above all the livestock and all the wild animals! You will crawl on your belly and you will eat dust all the days of your life. And I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will crush your head, and you will strike his heel.”

To the woman God said, “I will greatly increase your pains in childbearing; with pain you will give birth to children. Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you.”

To Adam, God said, “Because you listened to your wife and ate from the tree… cursed is the ground because of you; through painful toil you will eat of it all the days of your life. It will produce thorns and thistles for you, and you will eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.”

Genesis 3 ends with “God [banishing Adam] from the Garden of Eden to work the ground from which he had been taken” (Genesis 3:23). And “after [God] drove the man [and presumably the woman] out, he placed on the east side of the Garden of Eden cherubim and a flaming sword flashing back and forth to guard the way to the tree of life” (Genesis 3:24). God’s people have rejected God’s rule, they have been thrown out of God’s place, and there is seemingly no way back.

As we noted earlier, Genesis 3 exemplifies the pattern of human rebellion against God. The story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden illustrates the nature not only the nature of sin but also its inevitable consequences. And given that all of us are identified with Adam both in our humanity and in our sinful nature, we should not be surprised that these verses describing the pattern of God’s judgement point to profound consequences for all people everywhere.

(1) Death

Firstly, there are consequences for the relationship between God and human beings. In contrast to the picture of life in the company of God described in Genesis 2, in the post-Fall world we find ourselves banished from God’s presence and destined to die (Genesis 3:23-24, cf. Ecclesiastes 7:2, Psalm 82:6-7, Hebrews 9:27). Moreover, beyond our physical death we face the prospect of spiritual death, described in the Bible as the “second death” (e.g. Revelation 2:11, Revelation 20:6,14), the permanent separation from the God who is the very essence of goodness, truth and love. This is the essence of what the Bible calls hell.

Sin and death are inextricably linked. In the words of Paul, “the wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23, cf. Proverbs 10:16, Ezekiel 18:20). As sin is universal, so is death. Everyday experience bears this out. Death is even more certain than taxes. Everybody sins and, with almost no exceptions, everybody dies. (Enoch in Genesis 5:23-24 and Elijah in 2 Kings 2:9-11 are very much the exception rather than the rule.)

We can be thankful for the advances of medical science, and we may talk optimistically of saving lives, but it would be no less accurate to talk of deferring death. The ageing process is relentless (cf. e.g. Ecclesiastes 12:1-5). As time goes by, our looks diminish and our strength wanes. The inevitable deterioration of our bodies and our minds, whether gradual or sudden, points uncomfortably to our common destiny. In the poetic words of David, the days of human life “are like grass, [which] flourishes like a flower of the field; the wind blows over it and it is gone, and its place remembers it no more” (Psalm 103:15-16, cf. e.g. Ecclesiastes 12:7).

As we go through life, it becomes apparent that all of us live in the “shadow of death” (Psalm 23:4, cf. Matthew 4:16), be it in the context of accident, illness, natural disaster, terrorism, war, or merely old age. Sooner or later we learn at first hand that death is a terrible thing, and that no one gets out of life alive. Even when we think we have come to terms with the inevitability of death, it is still an incongruous and unwelcome intrusion into our lives. When people speak of untimely death, we know what they mean. But is death ever timely? We somehow know that we were made to live not to die. Death always somehow feels wrong, even when we are expecting it. It may not surprise us, but it shocks us nevertheless. The profound separation and sense of loss that death brings is a source of great pain and grief. And this is quite consistent with it being intrinsically linked with sin and separation from God. It should thus not surprise us that death is often a difficult subject to discuss.

(2) Toil

Secondly, there are consequences for the relationship between human beings and the world. In contrast to the well-watered and fertile land of Genesis 2:8-14, the ground is now cursed because of sin. Whereas in the Garden of Eden food was readily available, in the post-Fall world people eat “through painful toil” (Genesis 3:17) and “by the sweat of [the] brow” (Genesis 3:19). This is consistent with the frustrations we encounter in so many aspects of our work and life, even in parts of the world where food is plentiful. Material things need cleaning, servicing, repairing and replacing. Even our hobbies can have a tendency to regress to work.

The judgement concerning work and food production is spoken to Adam. The judgement concerning labour in childbearing (Genesis 3:16) is spoken to Eve. It is sobering to consider the nature of childbirth without the availability of medical intervention. And of course even with the best of modern medicine, there is pain – and not only physical pain – before, during and after childbirth, even when things go relatively well.

(3) Strife

Thirdly, there are consequences for the relationships between human beings. In contrast to the picture of paradise at the end of Genesis 2, we have already noted that in the post-Fall world Adam and Eve are quick to deflect the blame for their sin, a tactic that children rarely need to be taught. In itself, this tendency puts a strain on relationships, and so it is no surprise to see strife in the context of marriage as a further consequence of the Fall. It is not immediately obvious exactly what is meant by God’s words to Eve in Genesis 3:16: “Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you” (where the word translated “for” could also be translated “against”). Some indication comes a few verses later where God says to Adam and Eve’s firstborn son Cain that “sin is crouching at the door; its desire is for you, but you must rule over it” (Genesis 4:7 again, this time ESV, emphasis added). But in any case, Genesis 3:16 is quite consistent with the strife that occurs within marriage in the post-Fall world, where husbands and wives who were created to be one flesh are often found to be tearing themselves apart.

In Genesis 3 there is only one relationship between human beings but the pattern is familiar. More generally, the breakdown of our “vertical” relationship with God brings an inevitable breakdown in our “horizontal” relationships with other people. As D. A. Carson puts it, “the tentacles of rebellion against God corrode all relationships” (The God Who is There, p38). This is evident in relationships at all levels, from rivalry between individuals to wars between nation states. It is plain to see throughout the Bible, beginning with the first murder in the very next chapter of Genesis (Genesis 4:8). More broadly, it has been a recurring theme throughout human history. And of course the ultimate breakdown of our relationships with human beings – as with the ultimate breakdown of our relationship with God – comes with death.

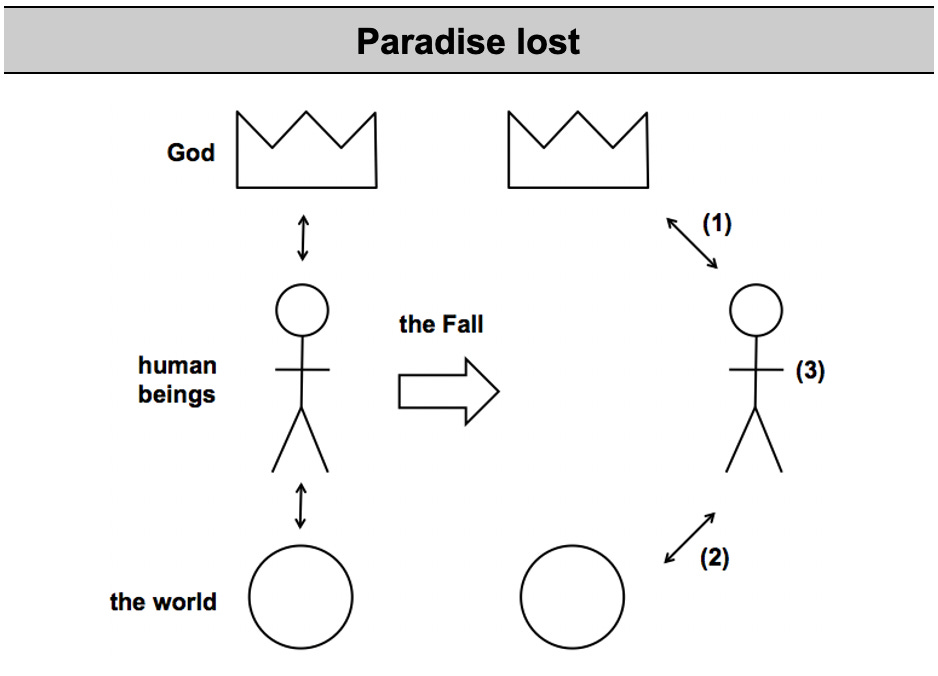

The first two chapters of Genesis present a picture of paradise: an ordered and purposeful world created by a good God in which his people live in his place under his rule. In contrast, Genesis 3 depicts the disordered and disrupted world in which we now live. As a result of sin, God’s people are no longer living in God’s place, they are no longer living under God’s rule, and they are destined to die. The picture is now of paradise lost. The numbers in the diagram below correspond to the headings (1), (2) and (3) above.

The image of God is marred

The consequences of human sin and divine judgement are evident in what we see now of the image of God in human beings. While we still bear the image of the creator God who is eternal, relational and holy, the image has been tainted to the extent that it is sometimes barely recognisable.

While we retain some degree of creativity, the work that this requires is often burdensome to us. We are inclined to idolise what we make and what we achieve, and we are slow to acknowledge and glorify the God without whom none of it would be possible. And we have put the products of human creativity, which are often neutral in themselves, to some terrible uses. While most of us are quick to appreciate the wonder and beauty of nature, we are inclined to worship “created things rather than the Creator” (Romans 1:25). And our desire for short-term material gain has often prevailed over our responsibility as God’s stewards of the earth, resulting in the abuse and exploitation of the natural world.

While we retain an awareness of eternity, we are inclined to focus disproportionately on this life, as if death in this world were the end of everything. While we are still often inclined to search for meaning and significance in our lives, we are typically disinclined to seek answers from the one who made us.

While we retain the capacity for relationship with God, we are inclined to hide from him, and in some cases to deny his existence altogether. While we retain our capacity to relate to other people, we are inclined to put our own interests first. While we retain the gift of language, it is in what we say that our sinful nature is often most evident (cf. e.g. Proverbs 10:19, James 3:1-11). While we retain the capacity to love, it is hatred that so often prevails. And even when things are generally going well relationally, we are inclined to value relationships with other people more than the relationship with the God who made us.

While we retain a sense of justice, many of us are inclined to turn a blind eye to injustice when it suits us. While we retain a sense of what is right and wrong, we are inclined to excuse our own sin. While we are quick to see fault in others, we are slow to see it in ourselves, and reluctant to recognise that we consistently fall short of God’s standards.

It is because we bear the tainted image of God that we human beings are a mass of contradictions. We are creative and yet destructive. We are aware of eternity but obsessed with the here and now. We are capable not only of self-sacrificial love but also of malicious hatred. We know the power of the moral law and yet we are inclined to exempt ourselves from its demands.

The complex nature of God’s judgement

The account of the pattern of God’s judgement on human rebellion in Genesis 3 is not exhaustive, but it is consistent with what we observe in the world. We are naturally inclined to put ourselves first, to ignore God, and to disobey his commands when it suits us. And as a result we are under God’s judgement with all that that implies.

That said, it is important to acknowledge that the early chapters of Genesis, and particularly the account of the Fall, leave many questions unanswered. On reading the accounts of the pre-Fall world, it is striking that relatively little is said about it. It is important to note both what the text says and what it does not say, and to avoid bringing our own preconceptions to it. The Genesis accounts do not say, for example, that there was no death or decay in the world before the Fall. Indeed it is plain from Genesis 1:29-30 that there was death for plants. And we may note again the distinction to be made between physical death, of the sort that would be required for an evolutionary explanation of origins, and spiritual death, which “entered the world... through sin” (Romans 5:12, cf. the “second death” we discussed earlier).

There is much more that could be said concerning the nature of God’s judgement. For the purposes of this book, the following general points are worth noting.

Firstly, the link between sin and judgement is not necessarily straightforward. There are many facets of God’s judgement that are complex and difficult to understand. Tempting though it may be to try, it is often difficult to discern a direct link between God’s judgement and a particular sin, and it is easy to jump to wrong conclusions (see e.g. Luke 13:1-5, John 9:1ff). Given the complexity of God’s ways and purposes, we should exercise caution in saying whether a particular event definitely is or is not the result of God’s judgement.

Secondly, God’s judgement is rarely immediately evident. While there are some spectacular biblical examples of instant judgements, and not only in the Old Testament (see e.g. Acts 5:1-11, Acts 12:21-23, 1 Corinthians 11:27-30), these are the exception rather than the rule. In general, God “causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous” (Matthew 5:45, cf. Jeremiah 5:24, Acts 14:17). He is “kind to the ungrateful and wicked” (Luke 6:35), for now at least. We may, if we do not think too hard, wish for more of God’s “instant” justice. But on reflection, and given that we all fall short of God’s standards, we should be glad that he does not operate that way. It is a reflection of his mercy that death is not instant, and that the world is not worse than it is. It is “because of God’s great love [that] we are not consumed” (Lamentations 3:22). God is by nature “compassionate and gracious… slow to anger” even in the context of the idolatry of his people (Exodus 34:6 again, cf. Exodus 32:1ff). And he is in general remarkably patient with his rebel creatures, “not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance” (2 Peter 3:9, cf. 1 Timothy 2:4, Ezekiel 18:23,32), a theme to which we shall return.

Thirdly, the nature of God’s judgement is often quite different to what we might expect. In Romans 1:18ff, when Paul describes how “the wrath of God is being revealed from heaven” against those who have rejected God, he repeatedly speaks of God “[giving] them over” to sinful behaviour (Romans 1:24,26,28). God’s usual response to sin is not to put a stop to it. It is to confirm people in their choice to rebel against him. A thunderbolt from heaven (or equivalent) is very much the exception rather than the rule. God does not generally act through what insurance companies call “acts of God”.

Lastly, it is important never to forget that we have only a partial view of what is going on. In the present, God’s judgement may sometimes seem unfair from our time-bound perspective. It is reasonable to ask, as the prophet Jeremiah does, “Why does the way of the wicked prosper?” (Jeremiah 12:1, cf. Psalm 73:3). But it is important to recognise that there is a future dimension to God’s judgement as well as a present one. And in the final reckoning, from an eternal perspective, perfect justice will one day be done (cf. e.g. Psalm 73:16ff).

An intractable problem?

The situation is serious…

I have sought to describe the problem of sin at some length. Without an understanding of the context, the nature and the gravity of the problem, it is difficult to see why a solution is needed, let alone why the solution takes the form that it does. As with most people, there is a part of me that would prefer to avoid thinking about sin, let alone talking or writing about it. But if I have a problem with my health, and I am seriously ill, I do myself no favours by refusing to address the situation. If I am not well, it is important to think things through, to find out more, and, above all, to take action. And if I do not act, there will be grave and inevitable consequences. The problem concerning my spiritual health may be less obvious, but, for the reasons we have discussed, it is even more important that it is addressed.

But how can the problem be addressed? So far at least, this is not the sort of revelation we might have hoped for. Things look bleak, with no obvious prospect of a solution to the problem. We might reasonably wonder why God has done things in the way that he has. Why did he make the world like this? Could he not have done things differently and better? These are not unreasonable questions to ask from a human perspective, but we need to remember that our perspective is just that: human. As Job recognised, we are time-bound mortals asking questions of an eternal, transcendent and immortal God whose “wisdom is profound” and whose “power is vast”. “Who has resisted him and come out unscathed?” asks Job (Job 9:4). “He is not a man like me that I might answer him, that we might confront each other in court” (Job 9:32). As we noted earlier, God’s relationship to people is not a relationship of equals. Whether we realise it or not, we are wholly reliant on his mercy.

…But all is not lost

But while the situation for humanity after the Fall appears bleak, there are some signs even in the account of the Fall that all is not lost. There are signs of God’s mercy even as he pronounces judgement.

In Genesis 3:15 God says to the serpent, “I will put enmity between you and the woman [Eve], and between your offspring and hers; he will crush your head and you will strike his heel”. Implicit in this verse is the promise of a man who will somehow defeat the serpent, albeit at a cost to himself.

Although Adam and Eve face permanent separation from God, they are not struck down dead immediately. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see the craftiness of the serpent in saying to Eve, “You will not surely die” (Genesis 3:4). Suggestive or ambiguous half-truths can do much more damage than outright lies. Death is surely coming, but it is not instant. And in his mercy God does not leave his people with mere fig leaves to protect their dignity. He makes “garments of skin for Adam and his wife and [clothes] them” (Genesis 3:21) before they are banished from the Garden of Eden.

While work has become a painful toil, this does not mean that things are as bad as they could possibly be, or that there is no satisfaction to be had in our work. Even in a fallen world it seems that work retains some of its inherent character as a part of God’s good creation (cf. Genesis 2:15).

And while childbearing has become much more painful, it is clear that Eve will still have children. Indeed we are told that she will “become the mother of all the living” (Genesis 3:20). It is no coincidence that Eve sounds like the Hebrew for life-giver and resembles the word for living. And as we shall see, it is from the children of Eve that the serpent-crusher of Genesis 3:15 will ultimately come.

Next chapter (Chapter 6)

Outline of whole book for reference

Part (i): Background

Part (ii): Problem

Part (iii): Solution

Main index with additional outline structure

The Big Reveal homepage (or search Substack for “The Big Reveal”)

Text © The Big Reveal 2024