Chapter 4: The context

God, human beings, and a picture of paradise

[ Index | (i) Background: 1 / 2 / 3 | (ii) Problem: 4 / 5 / 6 | (iii) Solution: 7 / 8 / 9 ]

The purpose of this book is to provide a carefully considered explanation of Christian revelation. In Part (i) we considered some important background. In Part (ii) we shall discuss the problem that God has disclosed through his revelation to us. As we proceed, I hope to demonstrate that what we read in the Bible is consistent with what we observe in the world.

In this chapter we shall discuss the context for the problem. In Chapter 5 we shall consider the problem itself. And in Chapter 6 we shall explore how the Old Testament describes the search for a solution.

4A. God

The book of Genesis

Christian revelation begins with the book of Genesis, which, as its name suggests, concerns how things began. As such, Genesis provides important context for the whole of Christian revelation.

Of all the books of the Bible, Genesis is one of the most misunderstood. Because of its centrality to the discussion that follows, we shall consider some relevant background information both before we begin and as we proceed.

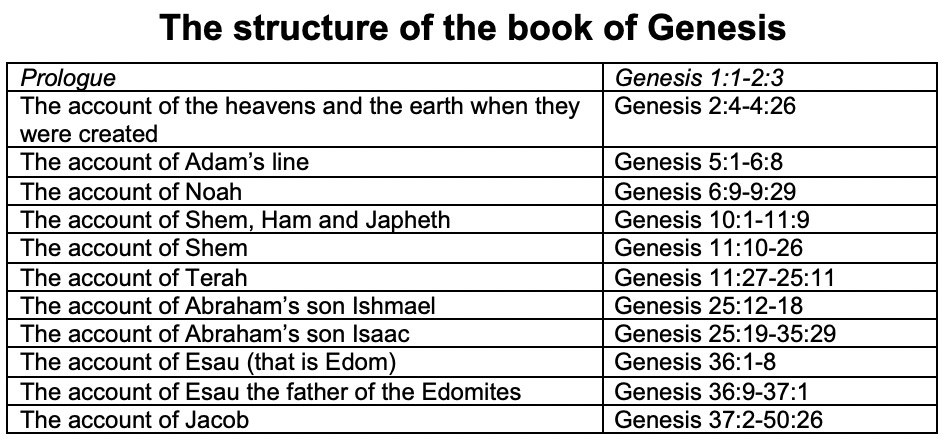

The book of Genesis can be considered as consisting of a prologue followed by eleven sections, each of which begins “This is the account of…” (NIV) or, more literally, “These are the generations of…” (ESV). In this chapter, we shall be concerned mainly with the prologue and the first of these eleven sections.

As we noted in Part (i), a careful consideration of both genre and context is important for understanding any part of the Bible. This is especially the case for the early chapters of Genesis. As we shall see, there is a good case to be made that this part of the Bible should not be read too literally, and that the rationale for this comes from a careful consideration of the biblical text. We should note too that there is good evidence that the opening chapters of Genesis were written in part to refute ideas about creation that were common at the time that it was written. As Gordon Wenham notes, the way in which God is presented in Genesis is “a rejection of the [then] common notion that matter pre-existed the gods’ work of creation”. And the “concept of man… is markedly different from standard Near Eastern mythology” (Genesis 1-15, World Biblical Commentary, p37).

The “six days” of creation

In the early chapters of Genesis we find two complementary passages on creation: (a) the Genesis prologue (Genesis 1:1-2:3), and (b) the opening part of the first of the main sections (Genesis 2:4-25).

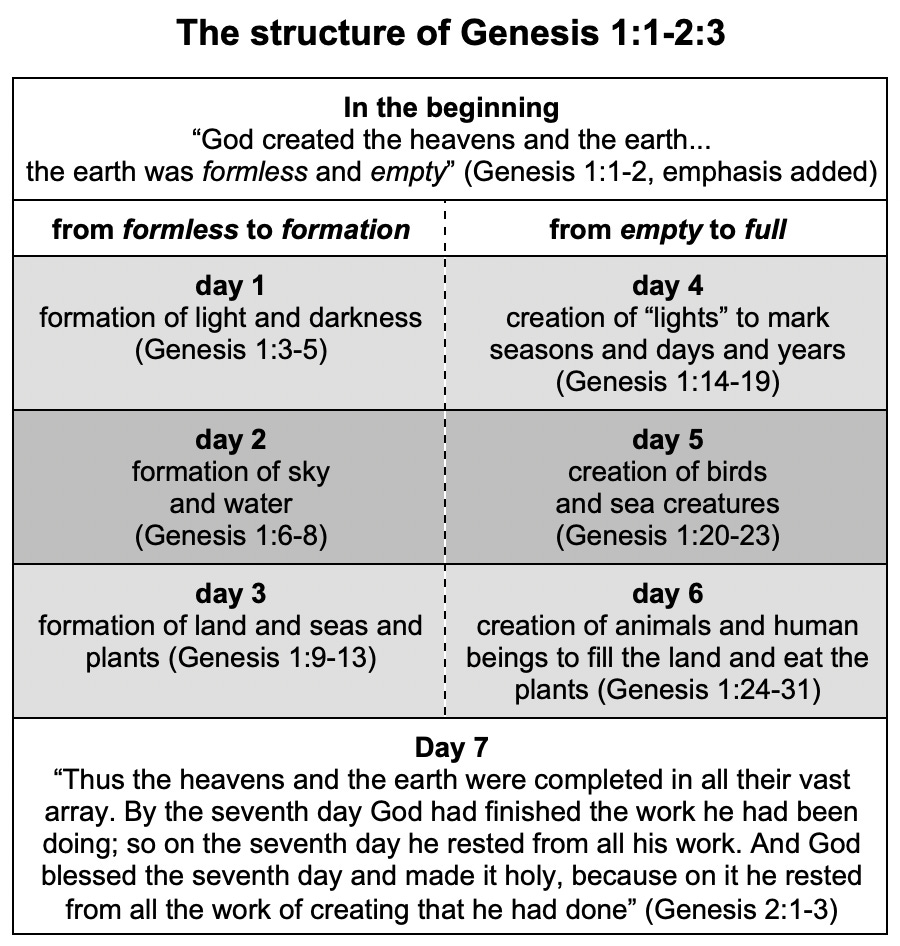

The prologue provides an overview of creation. As can be seen from the table below, the passage is carefully structured. In particular, we may note the parallels between days 1 and 4, days 2 and 5, and days 3 and 6.

The structure of the Genesis prologue is even clearer in the original Hebrew, which contains various literary devices that are not necessarily evident in translation. For example, in the Hebrew text of Genesis 1 there are several occurrences of the number seven, which is often used as the number of completeness and perfection in the Bible. Some of these, such as the seven “days” of creation, are hard to miss. Others are much less obvious. In the original Hebrew for example, the first sentence (Genesis 1:1) contains seven words, and the second sentence (Genesis 1:2) contains 2 x 7 = 14 words. Furthermore, the words for “heaven” and “earth” appear 3 x 7 = 21 times, and the word for “God” appears 5 x 7 = 35 times. When reading and interpreting the Genesis prologue, it is important to bear in mind the writer’s use of these and other literary devices.

We shall consider the second of the two creation passages in detail later, but for now we may observe that it begins: “These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created, in the day the Lord God made the earth and the heavens” (Genesis 2:4, ESV, emphasis added). The fact that this second creation passage speaks of one “day” of creation whereas the prologue has six “days” of creation suggests that the days should not be taken too literally. We may note too that in the first passage it is not until the fourth “day” that God appoints the sun “to mark seasons and days and years”. The six days of Genesis 1 are but one of several literary devices used by the writer to emphasise the ordered and purposeful nature of God’s creation.

What God is like

Having discussed something of the nature of the early chapters of Genesis, we are now in a position to consider what those chapters – and indeed other parts of the Bible – have to say about God. But before we begin to consider what God has said about what he is like, it is important to dispel some common misconceptions. In view of the Flatland analogy of Part (i), and knowing the complexity of even our 3-D world, we might reasonably expect revelation concerning Someone or Something beyond our world to be mind-boggling. And so it is with God, at least in some ways. It is perhaps partly because of this that there is no shortage of ill-conceived ideas about God.

God is not, for example, like someone who designs and makes a watch, and then winds it up and goes away and leaves it ticking. Nor is he like some sort of cosmic referee intervening every now and then when he sees fit. He is not like a puppet-master constantly adjusting the strings when things go wrong. Nor is he like a benevolent old man with a beard, bearing a resemblance to Santa Claus. Such ideas of God may be commonplace, but they are human inventions, and they are at best misleading. As we shall see, such simplistic misconceptions of God cannot be derived from a careful consideration of God’s revelation to humankind as revealed through the Bible and in the person of Jesus Christ

In contrast to the false ideas above, the God of the Bible defies straightforward description. He is the one “who alone is immortal and who lives in unapproachable light, whom no one has seen or can see” (1 Timothy 6:16, cf. John 1:18). His greatness and understanding “no one can fathom” (Psalm 145:3). To attempt to define what God is like is akin to trying to describe the indescribable, something which is consistent with the imagery used in Ezekiel 1 or Revelation 4-5 for example.

But while a full understanding of God inevitably eludes us, at least in this life, we can know something of him from his revelation to us, as we shall see. We shall thus revisit the subject of what God is like in Part (iii) of this book, after we have considered some particularly important aspects of his revelation. Meanwhile, for the purposes of setting God’s revelation in context we may note four important things about God: namely that he is the creator of the universe, that he is eternal, that he is relational and that he is holy.

God is the creator

Firstly, God is the creator of the universe. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Genesis 1:1). We may note that the Bible does not say how God did this, or on what timescale (cf. the above comments on the “days” of the two creation passages). Indeed the focus in the Bible is less on the created, and more on the creator who has such power and authority that he speaks the universe into being (cf. John 1:1-3, Hebrews 11:3).

But it is not only that God creates. According to Genesis, God is in complete command and control of his creation. By his word he separates light from darkness and the land from the seas (Genesis 1:3-10). He puts lights in the sky to “serve as signs to mark seasons and days and years” (Genesis 1:14-15). He commands living things to “be fruitful and increase in number” (Genesis 1:22,28). God rules over his creation, he defines how it operates, and he sustains its very existence (cf. e.g. Job 12:10, Colossians 1:17). As Augustine put it, “nature is what God does”. Whether or not we recognise it, without God there is no life. God is the one “for whom and through whom everything exists” (Hebrews 2:10, cf. Nehemiah 9:6, Acts 17:28). “Everything in heaven and earth” belongs to him (1 Chronicles 29:11, cf. Psalm 24:1).

God is eternal

Secondly, the creator God is an eternal, uncreated, self-existent being. We are not given an explanation as to his origin. As we noted above, the Bible begins with the words, “In the beginning God…” Speaking through the prophet Isaiah, God declares that “before me no god was formed, nor will there be one after me” (Isaiah 43:10, cf. Isaiah 44:6). As such, he is unique, and he has no rivals. He is beyond compare. “I am God,” he says, “and there is no other; I am God, and there is none like me” (Isaiah 46:9, cf. Exodus 3:13-14, Deuteronomy 32:39).

God’s existence is thus qualitatively different from the existence of everything else. While the existence of the universe depends on him, he does not depend on anything. God is in no sense a product of the world, be it through evolution or any other process. He transcends time. He is the “Alpha and the Omega… who is, and who was, and who is to come” (Revelation 1:8). “From everlasting to everlasting [he is] God… a thousand years in [his] sight are like a day that has just gone by” (Psalm 90:2-4, cf. 1 Chronicles 29:10, Malachi 3:6, Hebrews 13:8, 2 Peter 3:8). And he transcends space. “God is spirit” (John 4:24). Even “the highest heaven... cannot contain [him]” (1 Kings 8:27). We should not necessarily expect to find God within the world that he has created. But while God is ordinarily invisible to us (cf. Matthew 6:6, 1 Timothy 1:17), his eyes “range throughout the earth” (2 Chronicles 16:9, cf. Job 28:24, Proverbs 15:3, Zechariah 4:2,10). “Nothing in all creation is hidden from God’s sight” (Hebrews 4:13, cf. Psalm 139:1-7, Proverbs 5:21, Jeremiah 23:24).

Such observations are consistent with the Flatland analogy of Part (i). While an eternal, uncreated, self-existent God who transcends time and space is difficult to comprehend, this should not surprise us. And while it is not unreasonable to ask questions concerning the nature of such a God, we may note that, given the above, it makes no logical sense to ask questions like “Where did God come from?” or “Who created God?” To do so is perhaps a little like asking what is north of the north pole.

God is relational

Thirdly, the eternal creator God is relational. There is relationship even within God’s very being, between God the Father, God the Son and God the Spirit. Even at the very beginning of the Bible, before the creation of the world, we read of “the Spirit of God” being present and yet in some sense distinct from God himself (Genesis 1:1-2). It is the recurrent testimony of Scripture that God is One and yet somehow also Three, i.e. Father, Son and Spirit (cf. Matthew 28:19, Mark 1:9-11, 2 Corinthians 13:14). This notion of the “Trinity” is famously difficult to understand but this should not surprise us given the other indescribable aspects of the nature of God. And we may note in passing that the Trinity does not look like the sort of concept that someone would invent.

The relational character of God is reflected in the fact that he communicates with human beings. But God does more than merely speak. He demonstrates his relational character not just in what he says but in what he does. As we shall see in later chapters, God loves the world, and he loves every person in it. He cares particularly deeply about his relationship with people, and about the relationships that people have with one another. God is no “Unmoved Mover”, aloof from the world. Whether or not we recognise it, he is deeply involved with the world and its people.

That said, it is important to stress that God is in no way dependent on human beings. As the apostle Paul puts it, God “is not served by human hands, as if he needed anything” (Acts 17:25). God does not need us. He cannot be manipulated, and he deals with us on his own terms.

God is holy

Fourthly, the eternal and relational creator God is holy (cf. e.g. Leviticus 11:44-45). The word “holy” is often associated with “religious” people or objects, but this is at best misleading when it comes to understanding what it means for God to be holy. When God is referred to as holy in the Bible, it is in connection with his absolute moral perfection and purity. For reasons that we shall come to, God’s holiness is particularly difficult for us to understand. But if we are even to begin to understand God’s revelation, it is essential to appreciate at least something of the holiness that is intrinsic to his character.

According to the Bible, God is more than good; he is the unchanging source of all good things (James 1:17) and the essence of goodness itself (Mark 10:18). And God is more than truthful; he is the truth (John 14:6, cf. John 10:30, Isaiah 65:16). And as we noted above, God is more than loving; he is love (1 John 4:8-10). God is “compassionate and gracious” and “slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness” (Exodus 34:6). “His works are perfect, and all his ways are just... [He is] a faithful God who does no wrong” (Deuteronomy 32:4). As such, he is “a God of justice” (Isaiah 30:18), an important theme to which we shall return.

These are strong statements of course, and they raise some obvious and important questions. If all God’s works are perfect, why is there so much suffering in the world? If God is a God of justice, why does he permit so much injustice in the world? And more specifically, how can the moral perfection of such a God be reconciled with some of the events of the Old Testament? There is much that can be said in response to such questions, but it is beyond the scope of this book.

4B. Human beings

According to the Genesis prologue, human beings are a special part of creation. It was only after God had created human beings that he pronounced “all that he had made” to be not merely good but “very good” (Genesis 1:31, emphasis added). According to Genesis 1:27-28, “God created man [i.e. human beings] in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. God blessed them and said to them, ‘Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.’”

Created in the image of God

The phrase “image of God” is often misunderstood and sometimes grossly misrepresented. We tend to think of an image in terms of something visual. But the image of God – who is “unseen” (Matthew 6:6) – necessarily relates to character rather than appearance. As human beings, our natural inclination is to make God in our image, and to think of him as something like a bigger and better version of ourselves. But this is a topsy-turvy way of thinking. The image of God concerns people resembling God – at least to some degree – rather than God resembling people. It does not follow that if people have a given characteristic, God necessarily also has it.

Having previously noted four important things about the character of God, we shall now consider how these qualities are reflected in human beings made in his image. As we do so though, it is important to bear in mind that, for reasons we shall come to, the image of God in human beings has become tainted.

Created in the image of the God who is the creator

Firstly, and like the God in whose image they are made, human beings are inherently creative. Among the creatures of the natural world, human beings are exceptional. It is human beings who invent, research and discover. It is human beings who create great works of art, music and literature. Our ability as human beings to emulate God’s creativity, albeit in ways that are but a shadow of what he can do, is consistent with our being made in his image.

Human beings also have a particular capacity to appreciate God’s creativity. The works of God “are pondered by all who delight in them” (Psalm 111:2). God “has made everything beautiful in its time” (Ecclesiastes 3:11), and the beauty and intricacy of the natural world have become particularly evident as we have discovered more about it. Our capacity to appreciate God’s creation – to “think God’s thoughts after him” in words often attributed to Johannes Kepler – is consistent with our being made in his image.

As God’s image-bearers, uniquely able both to emulate and appreciate God’s creativity, we have a special responsibility for his world. As the creator of the world that he has made, God has appointed people to “fill the earth and subdue it” and to “rule over” nature (Genesis 1:26-28 again, cf. Psalm 8:5-8). This is not a licence to do whatever we please with the natural world, but a calling to exercise wise and responsible stewardship of it, in the knowledge that “each of us will give an account of ourselves to God” (Romans 14:12, cf. e.g. Proverbs 16:2, Hebrews 4:13).

Created in the image of the God who is eternal

Secondly, and again resembling the God in whose image they are made, human beings have an awareness of eternity. We bear the image of the eternal God who “has... set eternity in the hearts of men…” (Ecclesiastes 3:11).

In this context we should not find it surprising that we are inclined to wonder why we are here, and to ask questions about the purpose of life. We are inclined to search for meaning and significance in our lives. Like the Teacher of the Old Testament book of Ecclesiastes, most of us are uncomfortable with the idea that “everything is meaningless” (Ecclesiastes 1:1ff) or, more literally, “all is vanity” (ESV). This is consistent with the sense that many people have that our existence does not end when we die.

Created in the image of the God who is relational

Thirdly, and once again like the God in whose image they are made, human beings have a particular capacity for relationship. It is interesting to note that God’s words in Genesis 1:26 – “Let us make man [i.e. people] in our image” (emphasis added) – are themselves indicative of relationship even within God’s own being (cf. the earlier discussion of the Trinity). The fact that we are relational beings is a reflection of our being made in the image of God. We have the capacity to speak to each other because we are made in the image of a speaking God. We have the capacity to love because we are made in the image of the God who is love. We are made for relationship with other people, and, even more importantly, we are made for relationship with our creator.

This is not to say that God’s relationship to people is a relationship of equals though. It is true that some aspects of God’s relationship to people find parallels in human relationships, and we shall consider some of these in due course. But in some ways the relationship between God and the people he has created also resembles that of the potter and the clay. As Isaiah puts it, “We are the clay. [God is] the potter. We are all the work of [his] hand” (Isaiah 64:8, cf. Romans 9:19-21). It is important not to read too much into this analogy. It is but one of many biblical descriptions conveying something of the relationship between God and his people. Such imagery does not denigrate the intrinsic value of human beings bearing the image of God, but it does convey the relative lowliness of human beings in relation to the greatness of God (cf. e.g. Isaiah 40:15-26). As we noted earlier, we cannot deal with God on our own terms.

Created in the image of the God who is holy

Fourthly, and once more resembling the God in whose image they are made, human beings know about right and wrong (cf. e.g. Exodus 9:27, Luke 23:41). When we encounter injustice, we know that something is wrong. We typically long for justice, especially when we are the victims of injustice, and we consider ourselves right to do so. This is consistent with our being created in the image of a holy God – a God of justice whose ways are just, and who does no wrong.

It is not only that we have a sense of what is right and what is wrong though. We also have a sense that we ought to do what is right. As C. S. Lewis observes in Mere Christianity (book 1, chapter 2), one of the curious things we observe as human beings is that somehow, somewhere inside us, we sometimes find Something pressing upon us. For example, if I see an apparently innocent person being attacked in the street, I find, among various things, two opposite impulses: an impulse to stay and help, and an impulse to get away. In itself this is not so remarkable. What is more remarkable is that I find something else beyond these two impulses. I find Something – or perhaps even Someone – telling me that I “ought” to follow one of these impulses, and do what is “right”. Moreover, this sense of ought is often telling me to do the very thing that I do not want to do. Sometimes the impulse to get away is stronger, at least in some ways, than the impulse to stay and help. And yet Something – or Someone – tells me that I ought to follow the weaker rather than the stronger impulse, despite the danger.

Whatever this Something is, and however I seek to explain it, it transcends the impulses themselves. I did not in any way ask for or contrive this Something myself, and yet it impinges on me. I cannot escape this mysterious sense of ought. Whether or not I try to suppress it or explain it away or just ignore it, there it remains. It is not clear exactly what it is, or why it is there, or where it comes from. But this universal human trait is quite consistent with human beings being made in the image of a holy God.

Created male and female

We noted earlier that in addition to creating human beings in his own image, God created them male and female (Genesis 1:27). In some respects, the fact that human beings have been created male and female might seem barely worthy of comment. After all, almost all animals and birds have also been created male and female. But given that human beings are made in God’s image, and given that being made male or female is an intrinsic part of being human, it is worth considering briefly here some more of what the Bible says about the creation of men and women.

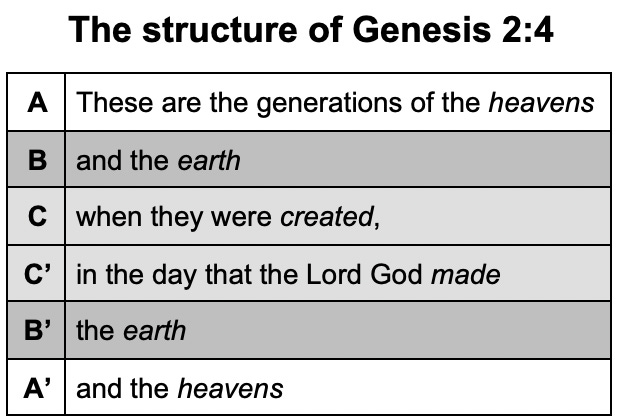

Genesis 2:4-25, the first part of the first of Genesis’ main sections, gives us important insight into (a) the relationship between God and his people, and (b) the relationship between men and women. As ever, it is important to consider carefully the genre and context of the passage. Like the prologue, the first of Genesis’ main sections is carefully structured. We shall see this in more detail when we consider Genesis 3 in the next chapter, but for now we may note that even the introductory verse (Genesis 2:4) has its own ABC-C’B’A’ structure, as is particularly evident from the more literal ESV translation (emphasis added):

It is also important to note here that Genesis 2:4-25 is written in a vivid and memorable way, borrowing imagery from other writings of the time.

In Genesis 2:7, we read that “God formed the man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.” This is consistent with our previous observation that God is the one who gives life and sustains it. (NB there is wordplay in the original text here: the Hebrew word for man (adam) sounds like the word for ground (adamah); it is also the name Adam.)

God then put the man in a garden he had planted in Eden, in which “all kinds of trees [grew] out of the ground – trees that were pleasing to the eye and good for food” (Genesis 2:8-9, cf. Genesis 1:29). And “in the middle of [this] garden were the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.” At this stage, everything is good. Genesis 2:10-14 speaks of a river watering the garden that separates into four smaller rivers, with the surrounding land rich in natural resources – in short, a wonderful place to live. When God places Adam in the garden “to work it and take care of it” (Genesis 2:15), this is not to be burdensome work. Adam is in a garden that is both beautiful and bountiful, and he is free to avail himself of its goodness. Only one thing is forbidden. In the words of God’s command to Adam, “You are free to eat from any tree in the garden; but you must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat of it you will surely die” (Genesis 2:16-17).

The Garden of Eden is a wonderful place with many good things, and yet God’s verdict is that “It is not good for the man to be alone” (Genesis 2:18). This is in striking contrast with the recurring verdict of “God saw that it was good” from Genesis 1, but the situation does not last long. Recognising Adam’s need for companionship, God creates “a helper suitable for him.” None of the birds or animals are deemed appropriate for this purpose, and so God creates a woman from Adam’s rib (Genesis 2:20-22). As Matthew Henry observed, “the woman was made of a rib out of the side of Adam; not made out of his head to rule over him, nor out of his feet to be trampled upon by him, but out of his side to be equal with him, under his arm to be protected, and near his heart to be beloved” (Matthew Henry’s Commentary on the Whole Bible). Like Adam, the woman is made in God’s image. And Adam evidently approves of his new companion, saying “This is now bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; she shall be called ‘woman’, for she was taken out of man” (Genesis 2:23). (NB there is more wordplay here: in the Hebrew, the word for woman sounds like that for man, and Adam’s response is a joyous poem.)

The narrator of Genesis then adds that, as a consequence of what has gone before, “a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and they will become one flesh” (Genesis 2:24). Sex and marriage are part of God’s good creation, and this verse, cited by Jesus in the New Testament in the context of a question about divorce (Matthew 19:3ff), provides a succinct summary of God’s pattern for sex and marriage:

(a) the man is to leave or forsake his parents, a particularly striking step in societies where honouring parents is especially important

(b) the husband and wife are to be united permanently in marriage (hence “till death us do part” in marriage vows); as Jesus puts it, “they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate” (Matthew 19:5-6)

(c) the husband and wife are to “become one flesh”, which represents not merely sexual union but a bond similar to that between blood relatives (cf. Genesis 2:23 again) which is, in terms of the imagery of Genesis 2, not only a union but a reunion

By implication, it is within the context of this marriage relationship that men and women are to fulfil God’s command to be fruitful and increase in number.

4C. A picture of paradise

A wonderful world

In the Genesis prologue, God’s consistent and repeated verdict on the world that he has spoken into being is that it is good. The word “good” is used a symbolic seven times, culminating with “very good” as God’s final verdict on his creation. This is consistent with the ordered and purposeful nature of creation portrayed in Genesis 1:1-2:3, and with the description of the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2:4-25.

In many respects, the world in which we live reflects its creator. It is important to be cautious here, for our experience of the world now is in some respects very different from what is was meant to be. For reasons that we shall come to, there is now a great deal that is wrong in the world. But despite this, the inherent goodness of the material world still reflects the inherent goodness of God. At its best, the world in which we live is an awesome, wonderful and beautiful place, and this is consistent with the biblical description of an awesome God (e.g. Psalm 47:2) whose “works are wonderful” (Psalm 139:14), and who “has made everything beautiful in its time” (Ecclesiastes 3:11 again).

It is also increasingly evident that the world in which we find ourselves is vast, strange and complex, and that its vastness, strangeness and complexity are far greater than anyone would have guessed. This too is consistent with God’s revelation to us. The vastness of the universe and the smallness and apparent insignificance of human beings on planet earth is not a recent discovery. Thousands of years ago, the Old Testament king David prayed to God, “When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, the son of man that you care for him?” (Psalm 8:3-4). Nor should the strangeness and complexity of our world surprise us. As God declares through the prophet Isaiah, “my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways... As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways” (Isaiah 55:8-9).

There is much more that could be said concerning how the world reflects its creator. According to the Bible, there are many important spiritual truths to be learned from merely observing what we see around us: from plants and seeds, for example (e.g. John 12:23-24); or from birds and animals (e.g. Matthew 6:25-27, John 10:1-18); or from our appetite for food and water (e.g. John 6:35ff, John 4:13-14). There is also much to learn from human relationships: from a king and his subjects for example; or from a husband and his wife; or from a father and his children. There are many ways in which the wonderful world around us reflects the character and purposes of God.

The “seventh day” of creation

As we noted earlier, the Genesis prologue describes not just six days but seven. After six days “the heavens and the earth were completed in all their vast array” (Genesis 2:1), but that is not the end of the matter. The goal of creation is evidently something beyond the mere existence of the human beings created on day six. “By the seventh day God had finished the work he had been doing; so on the seventh day he rested from all his work. And God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it he rested from all the work of creating that he had done” (Genesis 2:2-3).

The seventh day is quite different from the previous six. It has no morning or evening. It is an eternal day, blessed by God and made holy. As we noted earlier, the number seven often symbolises completeness and perfection, and the seventh and final day of the Genesis prologue is consistent with this.

Although God rests on the seventh day, this does not mean that he does nothing. As we shall see, there is a sense in which God is “always at his work” (John 5:17), but this work is evidently of a different nature to that of creation itself. As C. John Collins notes, the verbs in Genesis 2:1-3 are indicative: “the heavens and the earth were finished… God finished his work and rested… and God blessed the seventh day and made it holy. These events do not involve strenuous activity; they do not involve work at all. Instead they convey the mental actions of enjoyment, approval and delight” (Genesis 1-4, p70-71).

God’s people in God’s place under God’s rule

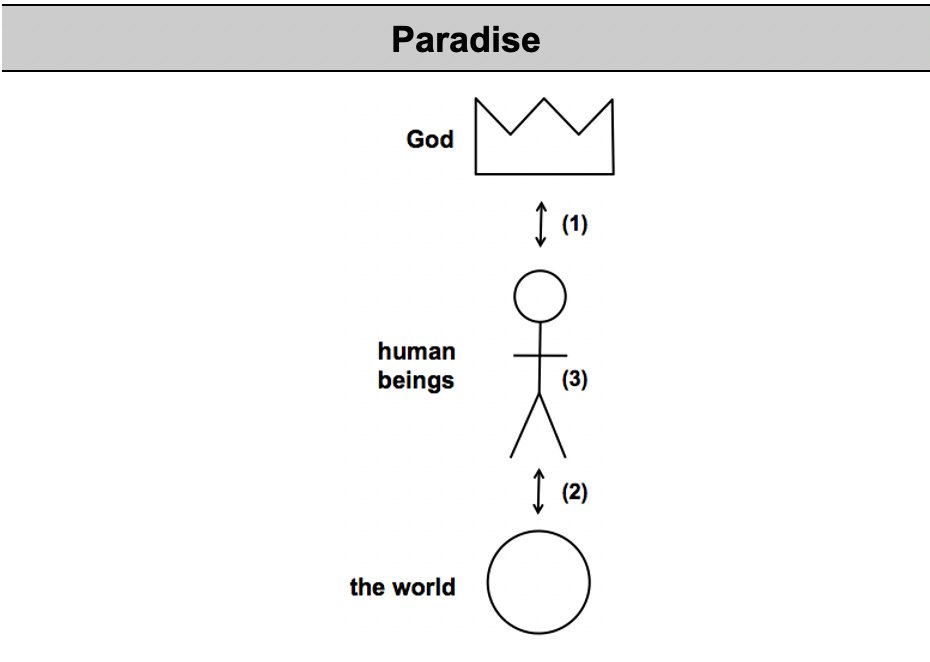

The first two chapters of Genesis present a picture of paradise: an ordered and purposeful world created by a good God in which his people live in his place under his rule. Three connected observations follow:

(1) The relationship between God and human beings is good

God’s people are living under God’s perfect rule. They are free to enjoy his creation, and he has delegated them responsibility to exercise wise and responsible stewardship of his world.

(2) The relationship between human beings and the world is good

God’s people are living in God’s beautiful and bountiful place. Adam is to work the garden to take care of it, and by implication his wife (later named Eve) is to help him. Such work is a blessing not a burden, and life is good.

(3) The relationship between human beings is good

Adam is pleased with the woman God has provided for him. And while Adam and his wife are “both naked… they [feel] no shame” (Genesis 2:25). (NB the word translated “shame” here does not carry overtones of personal guilt. The lack of shame described here is akin to that of young children unashamed of their nakedness.)

This picture of paradise provides the context for the rest of God’s revelation. The numbers in the diagram below correspond to the headings (1), (2) and (3) above.

Next chapter (Chapter 5)

Outline of whole book for reference

Part (i): Background

Part (ii): Problem

Part (iii): Solution

Main index with additional outline structure

The Big Reveal homepage (or search Substack for “The Big Reveal”)

Text © The Big Reveal 2024