Chapter 8: The solution

The remedy for sin, the revelation of God in Jesus Christ, and the new creation

[ Index | (i) Background: 1 / 2 / 3 | (ii) Problem: 4 / 5 / 6 | (iii) Solution: 7 / 8 / 9 ]

In Chapter 7 we considered Jesus Christ, the man who is God. In this chapter we shall discuss how Jesus provides a solution to the problem of sin outlined in Part (ii).

8A. The remedy for sin

The solution to the problem of sin

The serpent-crusher

For reasons that we have discussed, the solution to the problem of sin must involve the death of a human being who is free from sin. And because only God is free from sin, the solution must involve God becoming a human being and dying. But because God is immortal, he cannot stay dead. Resurrection is thus an inevitable part of the solution. And it is through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ that God provides the solution to the problem of sin: he becomes a human being who is free from sin, who dies, and who rises again.

In Jesus Christ, God’s promise of a serpent-crusher is fulfilled. Through the death and resurrection of the man who is God, Satan is defeated. In terms of the imagery of Genesis 3:15, Jesus Christ crushes the serpent’s head as the serpent strikes his heel. As one New Testament author puts it, Christ shared in the humanity of the children of God “so that by his death he might destroy him who holds the power of death – that is, the devil” (Hebrews 2:14).

This is not to say that Satan has yet been finally defeated. Because God transcends time, there are “now” and “not yet” aspects of the solution to the problem of sin, a theme to which we shall return. It is plain both from the Bible and from what we see around us that the world remains under the malign power and influence of “that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the world astray” (Revelation 12:9 again). But because of Jesus’ death and resurrection, the devil is now destined for destruction (cf. Romans 16:20, Revelation 20:10). Satan’s power is broken and “his time is short” (Revelation 12:12).

The one and only remedy for sin

Through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God provides the remedy for sin. Those who believe and trust in Jesus Christ can be identified with him in his sinlessness, and thus spared God’s judgement. As the apostle Peter puts it, “Christ… suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, to bring you to God” (1 Peter 3:18). And so, in the words of the apostle Paul, “if you declare with your mouth, ‘Jesus is Lord,’ and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Romans 10:9).

Salvation is, as John Stott observes, “a big and comprehensive word… [embracing] the totality of God’s saving work, from beginning to end” (“The Messenger and God: Studies in Romans 1-5”, in Believing and Obeying Jesus Christ, ed. J. W. Alexander (Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity, 1980), 10). In Jesus Christ, God deals with sin in the broadest sense. We noted earlier that sin amounts to more than mere human behaviour. Sin deceives us and enslaves us, and the whole world is its prisoner. But because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the whole world – not just people but the entire created order – will be liberated from the tyranny of sin. For Jesus Christ came to “do away with sin by the sacrifice of himself” (Hebrews 9:26).

But while in one sense Jesus Christ has done away with sin, it is plain that for now at least the world remains under its malign power and influence. It is important to understand that salvation concerns not just what has already happened but also what is happening and what is yet to happen. On a personal level, those who believe and trust in Jesus Christ can say: (a) that they have been saved from the penalty for sin; (b) that they are being saved from the power of sin; and (c) that they will be saved from the presence of sin. Because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the consequences of sin can – and will – be fully and finally reversed, a theme to which we shall return.

It should by now be evident that only Jesus Christ can provide the remedy for sin. As we have discussed, the problem of sin can be solved only by the man who is God. It should thus not surprise us that after Jesus claims to be “the way and the truth and the life” he goes straight on to declare that “no one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6). Jesus does not merely show us the way to God. He is the way to God. And neither should it surprise us when we read of theapostle Peter preaching that “salvation is found in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given to men by which we must be saved” (Acts 4:12, cf. Isaiah 43:11). As Paul puts it, “there is one God and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Timothy 2:5).

When Christians claim that Jesus Christ is the only way to God, it is not a claim without foundation. It may sound arrogant, especially when considered in isolation, or when stated inappropriately, but it is wholly logical and there are good grounds for believing it to be true. And if we have properly understood the problem of sin, we may reasonably ask how it could possibly be otherwise.

The gospel of Jesus Christ

The message of the remedy for sin that Jesus Christ provides is often known as the gospel. This is the same word used of the first four books of the New Testament, and it means good news. And as we shall see, the gospel of Jesus Christ is indeed wonderful news for those who accept it. It is, in the words of the apostle Paul, “the power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes” (Romans 1:16). And this gospel is encapsulated not in a philosophy but in a person: “Jesus Christ, raised from the dead, descended from David” (2 Timothy 2:8). In those nine words Paul captures the key elements of the gospel: Jesus Christ, his humanity, his death and his resurrection.

As such, the Christian gospel is quite different from other religions. As Tim Keller writes, “A gospel is an announcement of something that has happened in history, something that’s been done for you that changes your status forever. Right there you can see the difference between Christianity and all other religions, including no religion. The essence of other religions is advice; Christianity is essentially news. Other religions say, ‘This is what you have to do in order to connect to God forever; this is how you have to live in order to earn your way to God.’ But the gospel says, ‘This is what has been done in history. This is how Jesus lived and died to earn the way to God for you.’ Christianity is completely different. It’s joyful news” (King’s Cross, p15).

8B. The revelation of God in Jesus Christ

The essence of the Christian gospel is that Jesus Christ provides a remedy for sin. This is remarkable in itself. But what is even more remarkable is that in doing so he provides an unparalleled revelation of God. While we learn much of God’s character and purposes through his revelation to us in the Old Testament, the ultimate revelation of God comes through the person of Jesus Christ. We shall consider this revelation in terms of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection.

The revelation of God in the life of Jesus Christ

In the life of Jesus Christ we see the revelation of the character and purposes of the creator God who is eternal, relational and holy. The one through whom “all things have been created” (Colossians 1:16) lived on earth as a human being. The eternal Word of God “came down from heaven” (John 6:41, cf. John 3:13), became flesh and made his dwelling among us. The Son of God who is one with the Father came into the world to show us the extent of God’s love for his people.He demonstrated to us what it means to submit to God as Father. And he showed how God’s children should love one another (cf. e.g. John 13:34). The Holy One of God (John 6:69) lived a perfect, sinless life.

The life of Jesus Christ turns conventional wisdom on its head. We can but grasp at the wonder of the Incarnation of the God whose ways and thoughts are higher than our own (cf. Isaiah 55:8-9 again). Through what he says and does, Jesus Christ reveals the character and purposes of God.

As we noted in the previous chapter, Jesus, like his Father, is uncompromising on sin. He repeatedly exposes the hypocrisy of the outwardly religious, but he is unequivocal in condemning all forms of sin. According to John 8:2-11, he reminds those who wish to stone to death a woman caught in the act of adultery that they too are sinful, saying, “Let any one of you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” But he also says to the woman: “Go now and leave your life of sin.” Like his Father, Jesus demands nothing less than moral perfection. “Be perfect… as your heavenly Father is perfect,” he says (Matthew 5:48 again), in the context of having repeatedly made the point that true righteousness involves not only what we do and say but what is on our minds and in our hearts. And Jesus can demand moral perfection because, like his Father, he is morally perfect. He practised what he preached. And he lived a perfect life.

Like his Father, Jesus loves his people, but he cannot and does not ignore sin. Jesus knows that justice must be done and that sinners necessarily face judgement. And yet he loves us so much that he is prepared to die so that he might rescue us from sin, and free us from its consequences. Jesus longs for sinners – each and every one of us – to repent and be saved. He tells parables, such as the story of the lost son (Luke 15:11-32), that speak powerfully of the lengths to which God will go to seek and to save the lost.

It is one thing to speak of salvation though, and quite another thing to make it happen. As we have already discussed, it is hard to see how sinners can be saved at all. We saw back in Chapter 5 that God’s holiness means that justice is necessary. And we saw in Chapter 6 that God’s love means that he longs to save his people. But it is not easy to see how God can express love without compromising justice, and justice without compromising love.

The revelation of God in the death of Jesus Christ

It is in the death of Jesus Christ that we find the resolution of this tension. At the cross, divine love and divine justice come together. On the one hand, Jesus’ death demonstrates the justice of God. In the words of Paul, “God presented [Jesus Christ] as a sacrifice of atonement, through faith in his blood. He did this to demonstrate his justice, because in his forbearance he had left the sins committed beforehand unpunished” (Romans 3:25, emphasis added). And on the other hand, Jesus’ death demonstrates the love of God. As Paul goes on to say, “God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8, emphasis added, cf. 1 John 4:8-10).

In demonstrating his justice, God shows us how bad sin is. When we read “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son” (John 3:16), it is important to bear in mind that “the word ‘world’ in John’s gospel typically refers not to a big place with a lot of people in it but to a bad place with a lot of bad people in it” (D. A. Carson, The God Who Is There, p140). God’s love is remarkable not because of how big the world is but how bad the world is. And in demonstrating his love, God shows the extent to which he needs to go – and is prepared to go – to solve the problem. In the death of his Son Jesus Christ, God’slove can be expressed without compromising justice, and his justice without compromising love.

In the death of Jesus Christ we see further revelation of the character and purposes of the creator God who is eternal, relational and holy. The one through whom all things have been created did not just live among his creatures as a human being. He suffered and he died a terrible death at the hands of those he had created. The eternal Word of God did not merely come down from heaven to live. He came down from heaven to die. The cross has always been at the heart of God’s eternal plan to rescue his people. The Son of God who is one with the Father “loved [his people] to the end” (John 13:1). In going to his death on the cross, Jesus showed us what perfect submission to God the Father looks like. Though deserted by his friends and forsaken by Father, Jesus laid down his life, and gave the ultimate demonstration of sacrificial love. The Holy One of God who lived a perfect sinless life “was delivered over to death for our sins” (Romans 4:25).

The death of Jesus Christ turns conventional wisdom on its head. We can but grasp at the wonder of the cross. It is scarcely conceivable that a prophet of God would die as Jesus did, let alone the Son of God. And yet, as Jesus dies, the very worst that humanity can do to God is used by God to do the very best that he can do for humanity.

As Jesus dies, we have a striking picture of what man thinks of God. The religious leaders, having long plotted how they might kill Jesus (cf. e.g. Matthew 12:14) finally get their chance. “The chief priests and the elders of the people assembled in the palace of the high priest… they schemed to arrest Jesus secretly and kill him” (Matthew 26:3-4). Jesus Christ, who had lived a perfect life, full of grace and truth, was betrayed by Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples (Matthew 26:45-49). As we noted earlier, Jesus was arrested and brought to trial under false accusation (Matthew 26:50ff). He was deserted even by his disciples (Matthew 26:56). He was repeatedly disowned by Peter (Matthew 26:69-75), one of his closest disciples, who, along with the others, had declared his undying allegiance (e.g. Matthew 26:33-35). The religious leaders, who were powerful and influential people, persuaded the crowd to demand the killing of Jesus in exchange for the release of another prisoner (Matthew 27:20-22, cf. Acts 13:28). Pilate, despite recognising Jesus’ innocence, agreed to release Barabbas, who “had been thrown into prison for an insurrection in the city, and for murder” (Luke 23:19). The innocent Jesus Christ, Son of God the Father, was to die. The guilty Barabbas, whose name means “son of the father”, was to be set free. And so the man who is God was flogged, mocked, beaten, and then killed by crucifixion. As the one and only Son of God dies, the victim of lies, betrayal, injustice and murder, the problem of sin is laid bare. Nowhere is people’s hatred for God more starkly revealed than in the events which culminate in Jesus’ death.

As Jesus dies, we have a striking picture of what man thinks of God. But that is not all. We also have an even more remarkable picture of what God thinks of man. We may reasonably presume (cf. Matthew 26:53) that it was within Jesus’ power to destroy his enemies: those who plotted to have him killed; those who betrayed him, arrested him and falsely accused him; those who flogged, mocked, beat and crucified him; and those who were content to sit back and let it happen. And yet, “instead, [Jesus] entrusted himself to him who judges justly” (1 Peter 1:23). “He humbled himself by becoming obedient to death – even death on a cross!” (Philippians 2:8). Nowhere is God’s love for people more starkly revealed than at the cross.

The one who is cursed is redeeming others from the curse of the law

As God’s one and only Son dies, the solution to the problem of sin is revealed. It did not appear this way though. Humanly speaking, the death of Jesus Christ looked like a disaster. It is no wonder that Paul speaks of the “foolishness of the message of the cross” (1 Corinthians 1:18ff). Death was bad enough, but death on a cross was just about as bad as it could get. We saw in the previous chapter the brutal nature of crucifixion. We noted that for Jesus Christ death was exceptionally terrible because it meant separation from his eternal Father. But it is important also to observe that crucifixion was not merely excruciatingly painful but abjectly shameful. When men and women were crucified, they were crucified naked. Moreover, according to the Old Testament law, “anyone who [was] hung on a pole [was] under God’s curse” (Deuteronomy 21:23). It is thus hard to imagine a more ignominious end to Jesus’ life: dying a shameful death reserved for the worst criminals, and apparently cursed by God. As Jesus hung on the cross, “darkness” – a symbol of God’s judgement (cf. Exodus 10:21ff) – “came over all the land”. And as Jesus was about to die, he “cried out in a loud voice, ‘Eli, Eli,lema sabachthani?’ (which means “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’)” (Matthew 27:45-46).

All is not necessarily quite what it seems though. For the reality is that the one who is cursed is redeeming others from the curse of the law. Jesus’ death is not an accident. As we noted earlier, Jesus had explained to his disciples “that he must go to Jerusalem and suffer many things at the hands of the elders, the chief priests and the teachers of the law, and that he must be killed” (Matthew 16:21). Jesus knew all along that he had to die. He knew that it was written: “Cursed is everyone who does not continue to do everything written in the Book of the Law” (Galatians 3:10, cf. Deuteronomy 27:26). And he knew that the only way that people could be saved from this curse was for him – the sinless Son of God – to die. In the words of the apostle Paul, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us” (Galatians 3:13).

The one who cannot save himself is saving others

As Jesus dies, the chief priests, the teachers of the law and the elders mock him: “‘He saved others,’ they said, ‘but he can’t save himself!’” (Matthew 27:42). And humanly speaking, they are right. Jesus cuts a pathetic and helpless figure, unable to save himself from a terrible death.

Again though, all is not quite what it seems. For the reality is that the one who cannot save himself is saving others. Even as Jesus is dying we get a glimpse of the salvation that he offers: “One of the criminals who hung there hurled insults at [Jesus]: ‘Aren’t you the Messiah? Save yourself and us!’ But the other criminal rebuked him. ‘Don’t you fear God,’ he said, ‘since you are under the same sentence? We are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve. But this man has done nothing wrong.’ Then he said, ‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.’ Jesus answered him, ‘Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise’” (Luke 23:39-43).

The one who is dying is destroying death

During Jesus’ life, he had laid claim – explicitly and implicitly – to be the Son of God. But as he dies, this claim looks hollow. Those who have plotted to have Jesus killed mock him, saying, “He trusts in God. Let God rescue him now if he wants him, for he said, ‘I am the Son of God’” (Matthew 27:43). And leaving aside their tone and their motives, they have a point. How can this man, disgraced and dying, possibly be the Son of the Immortal God?!

Once more though, all is not quite what it seems. For the reality is that the one who is dying is destroying death. Jesus Christ really is the Son of God, and his death is achieving God’s purposes. Even as he dies we see a hint of the implications of his death: “At [the moment Jesus died] the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom” (Matthew 27:51). The curtain that symbolised the barrier between God and his people was completely torn in two, a theme to which we shall return.

It is in the events of Jesus’ death that the gulf between sinful people and a holy God is most apparent. It is not easy to envisage a more graphic scenario to illustrate people’s hatred for God and God’s love for people. As Jesus dies, the prospects for humanity look hopeless. The problem of sin remains. And the gulf between sinful people and a holy God appears more unbridgeable than ever.

As Jesus dies, God’s plan looks to be in tatters. But all is not as it seems. Jesus’ death is no accident. In the words of the apostles’ prayer to God recorded in Acts 4:27-28, “Herod and Pontius Pilate met together with the Gentiles and the people of Israel in [Jerusalem] to conspire against your holy servant Jesus, whom you anointed. They did what your power and will had decided beforehand should happen” (emphasis added). The death of Jesus Christ – the lamb “chosen before the creation of the world” (1 Peter 1:20) – had always been part of God’s eternal plan.

As we have seen, the cross appears to make a mockery of Jesus’ claims. But as Paul writes, the “foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom” (1 Corinthians 1:25). The cross is not what it appears. The reality is that God is using the worst of evil to achieve the greatest of good. In the death of Jesus Christ, we see the revelation of the character and purposes of the God whose thoughts and ways are higher than our own. But we cannot properly understand the cross in isolation from what follows.

The revelation of God in the resurrection of Jesus Christ

The cross reveals much about the character and purposes of God, but it is not the end of the story. Indeed it cannot be if God is immortal and Jesus Christ is the exact representation of his being.

In the resurrection of Jesus Christ we see yet more revelation of the character and purposes of the creator God who is eternal, relational and holy. According to the eye-witness accounts of the New Testament (e.g. Matthew 28:1ff, Luke 24:1ff), the one through whom all things have been created was raised from the dead. And Jesus’ resurrection marks the beginning of a new creation, a theme to which we shall return. The eternal Word of God did not merely come down from heaven to live and to die. He came down from heaven in order that he could conquer death and offer eternal life. The Son of God who is one with the Father did not just come to earth to live and to die. He came to rise again and thus provide a means by which God’s relationship with his people could be restored. He “was appointed the Son of God in power by his resurrection from the dead” (Romans 1:4). And he is now “seated at the right hand of God” (Colossians 3:1). The Holy One of God was not only delivered over to death for our sins. He “was raised to life for our justification” (Romans 4:25 again). Because Jesus was sinless, and because he died and rose again, those who believe and trust in him can be “justified”, i.e. declared righteous before God.

The resurrection of Jesus Christ turns conventional wisdom on its head. We can but grasp at the wonder of someone rising from the dead never to die again. For Jesus Christ, death was not the end. God raised him from the dead, and this changes everything.

The one who appears utterly powerless is revealed as supremely powerful

As Jesus dies, he is utterly powerless. He has been flogged – in itself a savage punishment that some did not survive. He has been beaten. And he is unable to carry his cross (Matthew 27:32). Even his clothes now belong to someone else (Matthew 27:35, cf. John 19:24 and Psalm 22:18). As Jesus is nailed to the cross to die, despised by his enemies and rejected by his friends, it is hard to see how he could have done more to render himself impotent.

But all is not as it seems. Jesus had said to his disciples not just that he must suffer many things and be killed but that “on the third day [he would] be raised to life” (Matthew 16:21). Jesus knew that he had to suffer and die; but he also knew that he would rise again. And Jesus’ resurrection transforms everything. In the context of the resurrection, the cross – which is in human terms the epitome of powerlessness – assumes remarkable power (cf. 1 Corinthians 1:17-18). It is not only that the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom. It is that “the weakness of God is stronger than human strength” (1 Corinthians 1:25). For the one who seemed completely impotent as he died on the cross has been “appointed the Son of God in power by his resurrection from the dead” (Romans 1:4, cf. e.g. Revelation 1:13-18). The reality is that the one who appears utterly powerless is revealed as supremely powerful.

The one who is mocked as king is revealed as the “King of kings”

As Jesus dies, the religious leaders sarcastically mock not just his inability to save himself but his claim to be a king: “He’s the king of Israel! Let him come down now from the cross, and we will believe in him” (Matthew 27:42). And humanly speaking, Jesus’ claims to kingship are laughable. A king (or queen) in the ancient world typically had immense power – much more than most of the monarchs of today, whose role is often largely ceremonial. The idea of a king dying on a cross alongside criminals was unthinkable.

But again, all is not as it seems. Indeed there is a hint of what is to come even as Jesus dies. The repentant criminal crucified alongside him says, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom” (Luke 23:42, emphasis added). It is this criminal, rather than the religious establishment, who recognises Jesus’ true status. Again, Jesus’ resurrection transforms everything. The reality is that the one who is mocked as king is revealed as the eternal King of kings.

The one who appears defeated by death is revealed as having conquered death

During Jesus’ life, he had laid claim to be the way and the truth and the life. He had raised people from the dead, and he had promised people the hope of eternal life. But as he dies on the cross, apparently defeated by death, Jesus’ claims to be the Son of God seem to be dying with him.

Once more though, all is not as it seems. Even as Jesus dies, remarkable things happen. We noted earlier the tearing of the temple curtain. But that was not all. Matthew records that when Jesus died, “The earth shook, the rocks split and the tombs broke open. The bodies of many holy people who had died were raised to life. They came out of the tombs after Jesus’ resurrection and went into the holy city and appeared to many people” (Matthew 27:51-53). Matthew also records that “when the centurion and those with him who were guarding Jesus saw the earthquake and all that had happened, they were terrified, and exclaimed, ‘Surely he was the Son of God!’” (Matthew 27:54). In contrast to the religious leaders, those guarding Jesus – presumably hardened soldiers – recognised him as the Son of God even in his death.

Once again, Jesus’ resurrection transforms everything. His claims to be the eternal Son of the immortal God are spectacularly vindicated. The one who is mocked as the Son of God “has destroyed death and has brought life and immortality to light through the gospel” (2 Timothy 1:10). The reality is that the one who appears defeated by death is revealed as having conquered death.

It is through Jesus’ resurrection that God’s salvation plan becomes clear. It is hard to imagine a more graphic demonstration of his sovereign power. As Jesus is raised from the dead, the landscape is changed forever. There is now hope beyond measure. Jesus Christ provides God’s promised solution to the problem of sin. Through his death and resurrection, the Son of God bridges the apparently unbridgeable gulf between sinful people and a holy God.

As Jesus dies, God’s plan looks to be in tatters. But again, all is not as it seems. God’s power and will had decreed not just that Jesus would die but that he would conquer death. He is not only the lamb who was slain from the creation of the world. He is the resurrection and the life.

In the context of the resurrection, the claims of Jesus Christ make sense. The resurrection completes God’s salvation plan and we see the power of the cross. So while “the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing… to [those] who are being saved it is the power of God” (1 Corinthians 1:18). God takes the suffering and death of his one and only Son, and transforms it into a glorious triumph (cf. Colossians 2:15). Indeed it is “because he suffered death” that Jesus is “crowned with glory and honour” (Hebrews 2:9). The foolishness of God is indeed wiser than human wisdom.

8C. The new creation

Paradise regained

The eternal city

In Chapter 4 we considered the account of God’s good creation and the picture of paradise that it portrays. And in Chapter 5 we considered the consequences of God’s judgement on the rebellion of sinful human beings in terms of death, toil and strife. As a result of sin, the world as we know it now is very different from the picture portrayed in Genesis 2. And without a solution to the problem of sin the outlook is bleak indeed.

But as we noted earlier in this chapter, God has provided a solution, not just for specific sins but for sin at large. Because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the consequences of God’s judgement can be reversed. And in the age to come, there will be a restoration of the paradise portrayed in Genesis 1-2.

At the end of Bible, we find a description of what that restored paradise will look like (Revelation 21:1ff, cf. Genesis 1:1). Some aspects are similar to the Garden of Eden of Genesis 2. We see again the tree of life and the river of the water of life. (Revelation 21:9-22:2, cf. Genesis 2:4-17). But some things are different. The imagery is not now of a garden but a city – a place where many people live. And this “city does not need the sun or the moon to shine on it, for the glory of God gives it light, and the Lamb is its lamp” (Revelation 21:23). The curses of Genesis 3 have been abolished – “no longer will there be any curse” (Revelation 22:3, cf. Genesis 3:14,17). And God’s dwelling place is again among his people: “Now the dwelling of God is with men, and he will live with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God”(Revelation 21:3 again, cf. Jeremiah 31:33, Ezekiel 36:28). We see a picture of paradise regained, with God’s people in his beautiful and bountiful place under his perfect rule. In the age to come, there will be no more death or toil or strife.

(1) No more death

We noted in Chapter 5 that, as a result of sin, the relationship between human beings and God is marred. In this fallen world, all of us live in the shadow of death. We are destined not just for physical death, but spiritual death that results in permanent separation from God.

This is not to say that things are as bad as they could possibly be. It is a measure of God’s grace and mercy that while death is surely coming, it is not instant. Even in this fallen world, enough people have lived long enough to ensure that the human race has not just survived but thrived, filling the earth (cf. Genesis 1:28) as God commanded.

In the Old Testament we find further evidence of God’s grace and mercy in the provision of the sacrificial system through which his people can relate to him. This is a temporary arrangement, pointing back to the picture portrayed in Genesis 2, and pointing forward to the permanent solution that is to come.

The Old Testament sacrificial system points forward to the life that comes through Jesus Christ who is the ultimate expression of God’s grace and mercy. We have noted already that Jesus claimed to be the resurrection and the life, but this is not the end of what he says on the matter. “He who believes in me will live,” says Jesus, “even though he dies; and whoever lives and believes in me will never die” (John 11:25-26, cf. e.g. John 10:10). This is a striking statement for many reasons, not only for what it says about life, but also for what it says about death. Jesus’ resurrection does not mean that those who believe in him will not die a physical death. It means that, like Jesus himself, his followers will live even though they die a physical death. Like Jesus, they will be raised to new life so that they cannot die again. They will “not be hurt at all by the second [spiritual] death” (Revelation 2:11, cf. Revelation 20:6 again). As Jesus puts it to his disciples, “Because I live, you also will live” (John 14:19).

Because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, there will be an end to death. This is not to say that death has been fully and finally defeated. But it is to say that the power of death is now limited. For those who believe, death has lost its sting. Like the devil, death is headed for destruction. Death is, as Paul puts it, “the last enemy to be destroyed” (1 Corinthians 15:26, cf. e.g. Revelation 20:14). We noted earlier that “the wages of sin is death,” but that is not the end of the matter. It is not even the end of the sentence, which in full reads: “For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus” (Romans 6:23, cf. John 17:3 again). In the age to come “there will be no more death” (Revelation 21:4, cf. Isaiah 25:8). Because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the relationship between God and human beings can be restored.

(2) No more toil

We noted in Chapter 5 that, as a result of sin, the relationship between human beings and the world is marred. In this fallen world, life is very often a painful toil. We encounter struggles and frustration in many aspects of our work and life, and childbirth is particularly painful.

Again, this is not to say that things are as bad as they could possibly be. It is a measure of God’s grace and mercy that, even in this fallen world, work retains some of its inherent goodness as a part of God’s creation. And despite the pain of childbirth, the arrival of a newborn baby can still bring great joy.

In the Old Testament we find further evidence of God’s grace and mercy in the provision of two important images of “rest”. These echo the seventh day of creation and point forward to its future restoration. Like the sacrificial system, these are temporary arrangements.

The first of these images of God’s rest is the Sabbath. Through Moses, God commanded his people, “Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy. Six days you shall labour and do all your work, but the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work…” (Exodus 20:8-10). This commandment, the fourth of the ten commandments given to Moses, is expressly based on the pattern of the seven days of Genesis 1:1-2:3. God’s people were to set aside the Sabbath day to enjoy God’s blessing and provision, and to remind themselves of God’s good purposes in creation. The principle of the Sabbath was an integral part of the life of God’s people. Even the land was to have rest once every seven years (cf. e.g. Leviticus 25:1-7).

The second image of God’s rest is the promised land (Joshua 23:9-15, cf. Genesis 12:1, Deuteronomy 12:8-10, Joshua 1:13). This was another picture of God’s blessing and provision. And as we noted back in Chapter 6, for a time God’s people did live in God’s place – the land of Canaan – under God’s rule. This was something of a restoration of the situation at the end of Genesis 2, but it did not last.

Both the Sabbath and the promised land point forward to the rest that comes through Jesus Christ who is the ultimate expression of God’s grace and mercy. “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened,” says Jesus, “and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28). Those who come to Jesus Christ, believing and trusting in him, are promised spiritual respite in this life, and an end to toil in the next. The New Testament writer to the Hebrews picks up this theme, declaring that “the promise of entering [God’s] rest still stands” (Hebrews 4:1, cf. Psalm 95:7-11), adding that “there remains… a Sabbath-rest for the people of God, for anyone who enters God’s rest also rests from his own work, just as God did from his” (Hebrews 4:9-10, cf. e.g. Genesis 2:1-3, Revelation 14:13).

Because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, there is for God’s people the promise of genuine and permanent rest, just as God rested on the seventh day. As we noted in Chapter 4, such rest does not entail doing nothing; the verbs used of God’s rest in Genesis 2 convey enjoyment, approval and delight. But such rest will mean an end to work as we know it. In the age to come, there will be no more toil. Because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the relationship between human beings and the world can be restored.

(3) No more strife

We noted in Chapter 5 that, as a result of sin, the relationships between human beings are marred. In this fallen world, because of the breakdown in our relationship with God, there is an inevitable breakdown in our relationships with other people. We see ongoing strife in human relationships at every level: in our families, in our schools, in our workplaces, in our national institutions, and between nation states.

Here too, things are not as bad as they could possibly be. It is a measure of God’s grace and mercy that, even in this fallen world, there are many good things that can come from human relationships. And remarkably, as we have seen, God can work out his good purposes even when human relationships are at their worst.

In the Old Testament we find further evidence of God’s grace and mercy in the provision of his law. Having rescued his people from slavery in Egypt, God gave them commandments which were, among other things, intended to help them live in harmony with one another. Children were to honour their parents, for example. Murder, adultery and stealing were forbidden, as were giving false testimony and coveting others’ possessions (Exodus 20:1-17). Like the sacrificial system and the images of rest, the law was also a temporary arrangement. It acted as a reminder that the world is no longer as God intended (cf. e.g. 1 Timothy 1:9-11), and it pointed towards a time when God would put his law “in [the] minds” of his people and “write it on their hearts” (Jeremiah 31:33), a theme to which we shall return.

The Old Testament law points forward to Jesus Christ who is the ultimate expression of God’s grace and mercy. The reconciliation of God and human beings that comes through Jesus Christ brings reconciliation between human beings. Our relationship to God undergirds how we relate to other people.

Because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, there will one day be an end to strife. When people truly believe and trust in Jesus Christ, God begins a remarkable transformation in their hearts, and the way in which they relate to others begins to change, another theme to which we shall return. And in the age to come, human relationships will be completely transformed. There will be no more death. And “there will be no more… mourning or crying or pain” (Revelation 21:4 again). In contrast to Genesis 3, where the relationship between Adam (the bridegroom) and Eve (the bride) breaks down, Revelation describes an eternal “wedding supper of the Lamb” (Revelation 19:9) between Jesus Christ (the bridegroom) and the people of God (the bride). In the age to come, there will be no more strife. Because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the relationships between human beings can be restored.

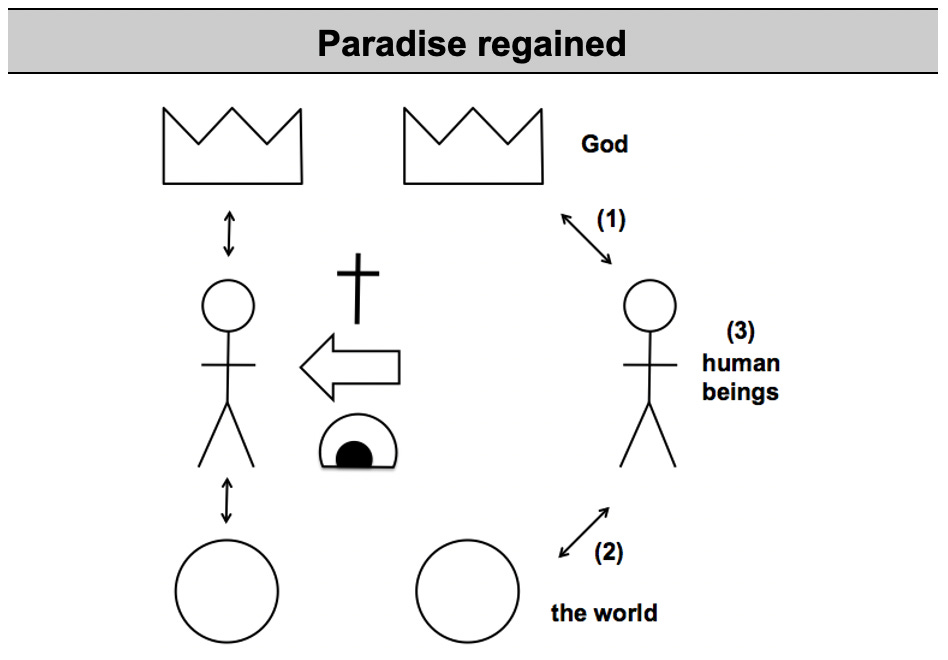

Because of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the consequences of God’s judgement can be reversed. There will come a time when God’s people will once again live in his beautiful and bountiful place under his perfect rule. But this time it will be permanent. The picture is of paradise regained. The numbers in the diagram below correspond to the headings (1), (2) and (3) above.

The image of God is restored

According to God’s revelation, the new creation will be free of the effects of sin that mar this fallen world. There will be no more death or toil or strife. But if the new creation is to be free of the effects of sin, it stands to reason that the people of the new creation must be free from sin. As such, God’s people need to be transformed. They need not only to be declared righteous in the sight of God, i.e. justified. They need to be made righteous in the sight of God, i.e. sanctified. The image of God, marred as it is by sin and its effects, must somehow be restored.God’s people must become like the one person in whom God’s image is perfect. They must be conformed to the likeness of Jesus Christ who is the image of the creator God who is eternal, relational and holy.

This process of sanctification – being made righteous in the sight of God – seems like an impossible task. And humanly speaking it is. It requires a miracle. According to Jesus, it necessitates being “born again” or “born of God” (John 3:3). As the notion of being born implies, the required transformation cannot be accomplished by human effort. It requires the power of the Spirit of God – “the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead” (Romans 8:11, cf. John 3:8, 2 Thessalonians 2:13).

By his Spirit, the Creator God begins to recreate those who believe and trust in his Son, Jesus Christ. “If anyone is in Christ he is a new creation” (2 Corinthians 5:17). As with our “first creation”, and indeed as with God’s creation at large, the process is slow but sure. It will not be completed in this life, but it will be made complete in the age to come. As Paul writes to Christians in the early church, “he who began a good work in you will carry it on to completion until the day of Christ Jesus” (Philippians 1:6). For “just as we have borne the image of the earthly man [i.e. Adam], so shall we bear the image of the heavenly man [i.e. Christ]” (1 Corinthians 15:49, cf. Romans 8:29). “By his power God raised [Jesus] from the dead, and he will raise us also” (1 Corinthians 6:14, cf. 1 Corinthians 15:43). Those who believe and trust in Jesus Christ “may take hold of the life that is truly life” (1 Timothy 6:19).

The new heaven and the new earth

The second coming

According to God’s revelation, in the age to come there will be “a new heaven and a new earth” (Revelation 21:1ff, cf. 2 Peter 3:10-13, Genesis 1:1, Isaiah 65:17) – essentially a new everything. As Paul puts it, the “world in its present form is passing away” (1 Corinthians 7:31).

According to what God has revealed, the emergence of the new heaven and the new earth will be preceded by the return – or the “second coming” – of Jesus Christ. We do not know when this will be. Indeed according to Jesus, “No one knows about that day or hour, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father” (Matthew 24:36). Only God knows when his Son will return.

We are told though that the second coming of Jesus Christ will be very different from the first. It will be sudden and its timing unexpected (cf. Luke 12:40, Luke 17:26-35, 1 Thessalonians 5:1-3). And it will be an event seen by all (Matthew 24:30, cf. Revelation 1:7). Jesus will “come back in the same way [that he went] into heaven” (Acts 1:9-11). But this time he will come “not to bear sin, but to bring salvation to those who are waiting for him” (Hebrews 9:28).

Heaven and earth reunited

In the present age, heaven and earth are estranged because of the effects of the Fall. But in the age to come those effects will be reversed, and heaven and earth will be reunited. Paul speaks of “[God’s] will… purposed in Christ, to be put into effect when the times will have reached their fulfilment – to bring all things in heaven and on earth together under one head, even Christ” (Ephesians 1:9-10). Heaven and earth will be part of the same whole. It should thus not surprise us when Jesus speaks of “the kingdom of heaven” belonging to “the poor in spirit,” and then of “the meek… [inheriting] the earth” (Matthew 5:3,5, emphasis added). We may note too that “heaven” is sometimes used in the Bible as shorthand for “the new heaven and the new earth” (cf. e.g. Matthew 6:20, 1 Peter 1:4).

The Bible says relatively little about the exact nature of the new heaven and the new earth. We should thus beware unwarranted speculation regarding the age to come. That said, there are some things which do seem clear enough.

Firstly, the biblical descriptions of the new heaven and the new earth suggest not so much the replacement of the existing heaven and earth as the regeneration of them. Jesus spoke of the coming “renewal [more literally regeneration] of all things” (Matthew 19:28, cf. Isaiah 35:1-7, Acts 3:21). And the voice from the throne of God that John hears says at the end of Revelation says, “I am making everything new!” (Revelation 21:5). As Paul puts it, in the age to come the world will be “liberated from its bondage to decay [more literally corruption]” (Romans 8:21).

Secondly, the primary focus of the new creation will be God and his Son Jesus Christ. The imagery of Revelation 4 is of a throne where God is worshipped as “the Lord God Almighty” who is holy and eternal (Revelation 4:8). And in Revelation 5 we find “a Lamb, looking as if it had been slain, standing at the centre of the throne” (Revelation 5:6). Like other parts of Revelation, this imagery – a Lamb standing but looking as if it had been slain – seems to be an attempt to describe the indescribable. For here we see glimpses of the glory of the risen and ascended Son of God who, along with the Father, is worshipped by the whole of the new created order (e.g. Revelation 5:11-13).

Thirdly, the relationship between God and his people will be perfectly restored. Through his death and resurrection, the Son of God has “purchased for God persons from every tribe and language and people and nation” (Revelation 5:9) – “a great multitude that no one could count” (Revelation 7:9). Jesus Christ has made God’s people “to be a kingdom and priests to serve… God, and they will reign on the earth” (Revelation 5:10, cf. Revelation 22:3). In contrast to this fallen world, “God’s dwelling place is… among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God” (Revelation 21:2-3). The greatest celebrations of this age are but mere shadows of the indescribable wonder of the age to come.

Finally, the new creation will be free from sin and its effects. “Nothing impure will ever enter [the Holy City], nor will anyone who does what is shameful or deceitful, but only those whose names are written in the Lamb’s book of life” (Revelation 21:27). The people of heaven will be perfectly holy – not because of their own righteousness, but because they have been made righteous by God. And because the new creation will be free from sin, it will be free of the effects of sin. God will wipe every tear from the eyes of his people. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, “for the old order of things has passed away” (Revelation 21:4).

Next chapter (Chapter 9)

Outline of whole book for reference

Part (i): Background

Part (ii): Problem

Part (iii): Solution

Main index with additional outline structure

The Big Reveal homepage (or search Substack for “The Big Reveal”)

Text © The Big Reveal 2024